Biography

Hard work, intuition and the nerve to take a chance describe T. Boone Pickens. A household name to the nation, Pickens is first an Oklahoman. His story ranges from earning a penny a paper as a young boy to making millions, and then billions. And then major losses. Many counted him out. But Pickens was far from out.

His modest upbringing provided the background for a work ethic that turned his remaining investment funds of $3 million into $8 billion in profit in just a few years. In 2008 The Pickens Plan was announced, designed to break America’s dependency on foreign oil. Boone invested $62 million to get the attention of the nation. And in 2010, America and Boone are waiting for a national energy plan. Pickens’ gift to his alma mater, Oklahoma State University remains the largest donation to a university’s athletic program in collegiate history. His total contributions to OSU amount to more than $400 million. Major academic gifts have also been made to the school, particularly to the School of Geology.

Full Interview Transcript

Chapter 1 – 0:47 Introduction

John Erling: Hard work, intuition and the nerve to take a chance describe T. Boone Pickens. A household name to the nation, Pickens is first an Oklahoman. His story ranges from earning a penny a paper as a young boy to making millions and then billions. And then, major losses. Many counted him out. But Pickens was far from out. And in this interview

Boone talks about his modest upbringing and how it led to his strong work ethic. He talks about his wins and his losses, his Pickens Plan and his contributions to Oklahoma State University. And in oral history fashion, Boone begins right now telling us about his family ancestry on VoicesofOklahoma.com.

Chapter 2 – 4:50 Birth

John Erling: This is John Erling, today’s date is August 6th, 2010, Boone if you will state your full name please.

Boone Pickens: Thomas Boone Pickens.

JE: Were you named after anyone?

BP: You know it’s kind of funny John that I’m a Junior, but really my dad’s name is not the same as mine. I know that you can put Junior on anything you want to. It’s a name. But my dad’s name is Thomas Boone Pickens, but he has a third name, Sibley. So his name is Thomas Boone Sibley Pickens. They didn’t give me that name, but they did put Junior on it. So when my dad died in 1988 I dropped Junior off my name.

JE: Your date of birth and your present age?

BP: May 22, 1928. I’m 82 years old.

JE: You might tell us where we are recording this interview?

T. Boone Pickens

Oilman and philanthropist

BP: In Dallas, in my office in Dallas, Texas at Preston Center.

JE: You said you were born in Holdenville? You might tell them just where exactly Holdenville is in Oklahoma.

BP: Holdenville is 10 miles from Wewoka, 40 miles from McAlester, and 20 miles from Seminole, 40 from Shawnee and 75 miles southeast of Oklahoma City.

JE: There is a story surrounding your birth. Your mother might have lost her life had it not been for your father. What is that story?

BP: Let me back you up as to the doctors involved. There were two brothers, the Wallaces, they bought the hospital in Holdenville and they are from Duncan. One of them was a surgeon, and one was a GP. My parents got married in 1923 and had difficulty. My mother couldn’t get pregnant and they made a trip to the Mayo Clinic and they told them just to go back and to continue to try. And she got pregnant in late 1927, because I was born in May of 1928. Now we get down to the birth date. And fortunately the doctor, one of the two brothers, the surgeon, was her doctor. So he took my dad in a room. My dad said there is a large book on the table across the room and he assumed it to be a Bible. And I’ve had my dad tell me this story I would say at least six times. He told it exactly the same way every time. He said they went in and he said, “Tom we may have a really difficult decision to make here. Grace can’t deliver, so you may have to decide who survives

here.” And my dad said, “No, we can’t do that.” He then talked about what the problem was, and why she couldn’t deliver. And my dad said, “But you’re not this far and he held up his fingers from that baby.” And it was an inch–that was all. And he said, “Surely you can save the baby and my wife too.” Then they went on to look at the book that was on the table, and it was a medical book. The doctor said, “This is what I have to work with.” He said, “I’ve got a page and half and one picture of a cesarean section.” My dad said, “Read it good and remember every bit of it because we’ve got to do it.” And he talked the surgeon into doing it. Before they left the room my dad said, “Let’s kneel down and pray.” And they did and my dad said he went outside and sat down. Some minutes after

that, the doctor walked through the room. My dad said, “How long?” And the doctor said, “I don’t know.” My Dad said, “I don’t know how long I’d been sitting here.” It could have been 5 minutes. It could have been 15 or 20 minutes, but not any longer. But he walked through the room, didn’t say anything to him, went into the operating room and came back out and he said, “You’ve got a boy and Grace and the baby are fine.” There was not

a cesarean birth in that Holdenville General Hospital until I think it was like 30 years later.

JE: Could it have been the first in Oklahoma maybe?

BP: I don’t know. It was 1928, we sure know when it was. But you know with that kind of start, you can kind of make anything out of it. One for sure was we were very lucky that we had the surgeon brother that was the doctor, because I don’t think my dad would’ve ever

talked the other doctor into doing that. I don’t think he could have done it. So that was a real break. But the biggest break was a dad that said, “No, you’ve got to get that baby out there. You’re only this far away from it. You can do it.” Just his leadership with the surgeon, to talk him into doing that, that was a real break for me.

JE: The fact that he had no doubt in his mind if he’d have waffled back and forth, it might have made a difference to the surgeon.

BP: I think, honestly, knowing my dad in the way he told the story that he never wavered.

He just said, “We’ve got to do it.”

JE: And then you were obviously then an only child?

BP: Yes, they told my parents then, they said you can’t ever try to have children or have children again because a woman that’s had a cesarean section can never have another child which now it’s very common to have several. My mother was born in 1900, so she was 28 years old. My father was born in 1897 so he was 31.

Chapter 3 – 6:21 Father/Mother

John Erling: Your mother’s maiden name?

Boone Pickens: Molonson. If you go back over the history of the family, it’s pretty interesting because my mother was very proud of my father’s heritage and of course her own, but said little about herself. But she knew that Pickens’ and Boones’ had a good lineage.

Andrew Pickens was second-generation. I am eighth-generation in the United States. She encouraged me. She said, “I want you to do a study on your family because you need to know where you came from.” And she had a file on it with half a dozen single sheets in it. After she died in 1977 I started to wake up in the night that I said that I would do that, and I hadn’t done it. So it was several years later, I think three or four years later, I hired to genealogists to go back and study the family and all. The Pickens and Boones, there were a lot of leaders, there were three governors of South Carolina and one from Virginia.

Gen. Andrew Pickens fought in the Revolutionary war and he was on the same line as Francis Marion and White Horse Harry Lee. He had a very distinguished record and is buried on the Clemson campus. That’s interesting because Clemson wants me to help them and a gentleman from there said, “Not only is your great-great-grandfather here on campus, but we have orange too just like Oklahoma State.” (Laughter) I haven’t given any thing to Clemson yet. Anyway, I was on the CNN program, this is got to be 25 or 30

years ago and they said, “Are you related to Daniel Boone?” This was before I did the research. I said, “Well, I think I am.” And the next day a woman called me and she said, “You don’t know me.” And she told me who she was. And she said, “Don’t get on national television anymore and say you related to somebody when you don’t even know whom you’re related to.” I said, “Straighten me out.” And she said, “You’re not a descendent of Daniel Boone. You’re a descendent of John F. Boone.” That caused me to move forward with the project too. John F. Boone came to Barbados from England and into Charleston, South Carolina. The Boones were related, yes, distantly in England. But I did not come from Daniel Boone, I came from John F. Boone. So that aroused my curiosity and attention too, maybe I had better watch out what I’m saying because people are watching what you say, which is good and that means they’re listening to you.

JE: John F. was he of note?

BP: Yes, he was from the Boone plantation out of Charleston, which is a destination point for people going to see the plantation back at that period. So yes, he was of note too. Then the Pickens, I made a comment down at Augusta one time. They said, “You know you’ve got a very interesting name in the South, the Pickens and Boones.” I said, “The Pickens are also married to the Calhoun’s.” The guy looked at me and he said, “John C. Calhoun?” And I said, “Yes, John C.” He said, “You’ve just arrived.” (Laughter) He said, “John C. was very important to the South. But the point I want to make is, having all of these people that I came from, I can tell you that the work ethic that I have came out of my mother’s genes. I never saw the Pickens (side of the family) as real hard workers, or the Boones either. They were wonderful people in all. But when you look at the Molonson’s, those people, they were hard, hard workers. I have those genes, and I, too, am a hard worker.

I love to work and I enjoy doing it.

JE: Your mother Grace, where did she grow up?

BP: She was born in Arkansas and when she was a year old they moved to Holdenville.

JE: Then we come to your father, where did you grow up?

BP: He was born in the Hugo, Oklahoma and my grandfather was a Methodist minister in Indian Territory in southeastern Oklahoma. He was also a minister there in Hugo and Durant. He ended his career in Tecumseh.

JE: And your grandfather’s name?

BP: His name was A.C.

JE: Your grandmother was very instrumental in your life?

BP: That was my grandmother Molonson, my mother’s mother. She lived next door. She had a great amount of influence because I was right there close to her.

JE: Describe your mother, what kind of personality did she have?

BP: She was a beautiful woman. She was small. She was 5’2” or 5’3” and very disciplined.

I heard her say many times “I’ll never weigh 120 pounds.” And she never weighed 120 pounds. (Laughter) She got close, but when she did she was so disciplined that she cut it back. She loved apple pie. I’ve seen her many times say, “Two bites is all I need.” And she’d push it back (down). I do that too. Not as much as she did. I remember very well how she did it. I’m a little overweight right now. I weigh 179 pounds. I weighed 168 for 25 years on Cooper physical exams that I did. The highest I’ve ever been is 183. I’ll never be there again I can tell you that. I’m coming down. I’ll get it back down to 170. (Laughter)

JE: And your father, describe his personality?

BP: He was not happy-go-lucky, but he enjoyed life when he was making money. He loved to fish and hunt. One time he went for a month from lake to lake within Indian guide in Ontario, Canada. The guy couldn’t even speak English and my dad was up there fly- fishing with him. My mother, it always kind of annoyed her. She would say, “Well, Tom,

what would the guide talk about?” He said, “We didn’t talk Grace, neither one of us could understand each other, so we didn’t talk.” She said, “I can’t imagine going a month and not talking to somebody.” And he said, “Well, we did but we were catching a lot of fish.”

JE: You are a hunter and fisherman today?

BP: I’m not an avid fisherman, but I am a hunter.

JE: You picked that up from your father?

BP: I did. I’ve never really been interested in anything other than wing shooting, birds. I’ve killed deer and killed elk and I’ve been to Africa once, but I have no interest in doing it again. I think I’ve only killed two deer in my life. I’m not a deer hunter.

Chapter 4 – 7:14 Pickens’ Garden

John Erling: Then there’s another lady called Aunt Ethel Reed?

Boone Pickens: Ethel Reed was my mother’s sister. She was five years older than my mother.

She lived to be 95. My mother had a brain tumor and she died in 1977.

JE: The three of them, your grandmother, your aunt and your mother, the three ladies were very close to you?

BP: That’s right.

JE: They had tremendous influence in your life.

BP: They sure did because they were always together and I never could split them up. They came together and he couldn’t shake them. (Laughter)

JE: So they always kept an eye on you? What did they call you when you were a child? Was it Boone or did they call you–?

BP: They called me Boone. My mother never liked T. Boone, because she said that’s going to turn out like T-bone.

JE: Yes.

BP: And she said, “I don’t want any nicknames, you go by Boone.” I said, “I want to go by Tom because I like it better. When I introduce myself as Boone, people usually say, ‘Ben’?”

And she said, “Well, you straighten them out, and if you have to, spell your name for them. But you need to tell them who you are. And there are a lot of Tom’s, a lot of George’s and a lot of Charlie’s, but not many Boone’s. Once you tell them your name, it will stick and they won’t ever forget it.”

JE: And your grandmother was Nellie?

BP: Yes.

JE: What kind of person was she?

BP: She had a great sense of humor, but your first look at my grandmother told you that she was pretty serious. My Dad, I’ve never seen him show respect for a woman like he did his mother-in-law. When he went over to her house he took his hat off and went in and left his cigar on the porch banister. And never went in her house and smoked. He smoked at home. He was respectful to my mother too, but especially to my grandmother. I caught on to that at some point, and I thought there’s more than respect here, he’s afraid of her. (Laughter) I really think that he was afraid of her. He never called her mother. He never called her Nellie. It was always Ms. Molonson.

JE: Was your father tall?

BP: My dad was 5’8” and my mother was 5’3”, and I’m 5’ 9.5”, so I got pretty lucky there.

JE: On handling your money, there’s a story about you going to town with 50 cents? And your grandmother would ask you, “What you doing? Where are you going with this money?”

BP: Well the way it was, she had a big garden. If you remember being born in 1928 we were in the middle of the Depression but it was never discussed at our table. I mean I don’t remember it being discussed. It was hard times and people were struggling and all, but I

don’t remember the word Depression being used. It could have been said and I just don’t remember. But I very well remember that my mother and dad both worked. My mother worked for the government. She was a manager of the rationing. She had huge counties, Seminole and Pottawattamie Counties, so she had a lot to do.

JE: And that was during the war years?

BP: Yes, that was during the war. So we are now talking about 1940. Let’s go back to the Depression and also the Dust Bowl, because those were going on at the same time.

I can remember very well that my grandmother had a big garden. And we ate out of the garden and they canned out of the garden. That garden actually was big in our lives the whole year, because we ate canned goods and all. The Molonson’s were very frugal

people. My grandmother could stretch a dime pretty far. I can still remember that she marched me back into her room in her home and she said, “Okay, this is the light switch. You see it turns it on and it turns it off. When you come in, if you can see well enough, you don’t turn it on. But one thing you do if you turn it on, when you leave the room you turn it off. Next month, if you continue to walk out of rooms and leave the lights on, you will get the light bill. And I will expect you to pay for it.” That made an impression on me.

JE: Do you think it affects you today?

BP: It sure does because I don’t leave this office at night without turning my lights off and if I’m in the conference room and about to leave from there, I will walk back around here and cut off my lights.

JE: But didn’t you say you were going to town with 50 cents and she would ask you–?

BP: Yes. I would run down the driveway. The driveway was between our homes. You know the kind with gravel on it. She had worked in her garden. In daylight she was in her garden working and everything. It was an immaculate garden and it was a big garden. As she was through, and I’m going to town, it was like nine o’clock on a Saturday morning because I wanted to get there early enough to get a haircut and then go to the movie and get a bag of popcorn. So I’m going down the driveway running to meet a couple of guys down on the corner. I stopped and she had taken her bonnet off and sat in the swing and she was swinging to get some breeze there. It was hot, really hot and I would come to an abrupt stop and slide on the gravel and say, “Good morning!” And she’d say, “Now sonny, where are you headed?” And I said, “I’m going to town.” And she said, “And what are you going to do?” And I said, “Well, I’m going to get a haircut.” And she said, “Well then you have money with you?” And I said, “Yes, I have 50 cents.” And she said, “Now tell me how you are going to spend that.” And I said, “Well, a haircut is 25 cents and then I’m going

to the movie and I’m going to spend a dime for the movie and then popcorn is a nickel and I’m going to buy a bag of popcorn.” And she said, “Now Sonny, you have money left over at that point, and I want to tell you that a fool and his money are soon parted. Don’t be a fool. Come home with your money.” And so the next week, the very next week

we’d go through the same routine. (Laughter) I would go down the driveway. She would ask, “How much money do you have?” You know and it was a constant. You were held responsible. You were accountable for what you had and for what you’re going to spend. I didn’t realize it at the time. I thought she doesn’t remember. Yeah, she remembers. The question is do you remember? That’s what it was. And she hammered away.

JE: Your aunt Ethel was a teacher?

BP: Yes, she was my schoolteacher.

JE: She taught you? So man, you couldn’t get away from these women could you? (Laughter)

BP: I could not get away from her. She and my mother, they were sisters. She had a son that

was very unusual. He was very smart. And he is very focused. He played the cornet, he sang in the choir and he was not an athlete and he was a very good student. I was more into sports. I tried to play the clarinet and was not any good. I tried to do piano and it was worse. Bob and I did not share the same interests. At the same time he was a great guy, and his father died. His father was 40 years old when he died. He had a heart attack. So my father was kind of a surrogate father for Bob. So the family was tight. I mean we were all there usually we ate supper together at night, not dinner. In the mid-30s, it was called breakfast, dinner and supper. Dinner was at noon but we ate out of the garden at night, and my dad didn’t like it when we didn’t have meat. He said, “We’re doing well enough that we can have meat.” And my grandmother said, “We will have Tom, but not every night.”

JE: So that meant you had to go out and buy beef or chicken and all?

BP: Yes.

Chapter 5 – 6:52 Boone’s First Deal

John Erling: But then you as a young boy had jobs, various jobs as a young man?

Boone Pickens: All of that was so routine. And never did you feel uncomfortable, but they would start to ask what are you going to do? What job do you have for the summer? Or are you going to work at the swimming pool? What are you going to do? And they would make it clear. It was subtle, but you knew the pressure was on that you would need to get this lined up now, not when the summertime comes. You get these things done before summer. I always had a paper route. But the Holdenville paper was just an evening paper. So you had six papers a week. You had plenty of time to do something else.

JE: Didn’t you acquire other routes? You had one route and then you made an acquisition?

BP: The Holdenville newspaper is owned by Tom Phillips. His daughter was the same age that I was and we were in school together and we were pretty good friends. Joy

Elaine was her name. She was a very smart girl. So I started out at the newspaper as a substitute. He would go and learn the route of the regular delivery boy, and if he was sick or something you could fill right in because he knew the route. I was a substitute for I don’t know I don’t think it was for very long. I think two or three months. And then, as the route opened up they moved up in size. The largest route was delivering 150 papers, and the smallest was 28 papers. That was Broadway of America if you can imagine that in Holdenville, Oklahoma, Broadway of America. (Laughter) It was one street, and it was 28 papers. But it had a clinic, and some apartment houses on it, so you got rid of a lot of papers on two or three spots. So anyway, I was given the Broadway route of 28 papers.

You made a penny a paper net a day. You could figure it out really easily. That’s not the way they paid you, but the way it came out you made a penny of paper. So I made $.28 a day on that route. I got that route in 1940. I was 12 years old when I got a full route. But then, I moved up, and I moved up in the same area. The route opened up next to me, so

I said, “Instead of moving me over to that route, and there’s not anybody in line why don’t you just give me that route?” And that was 44 papers + 28 papers so now I’m up to 70 papers. They said, “Okay, that makes sense.” Then, lucky me, a route opened up on the other side of my original route and I went back with the same story. And this was right in town, two blocks from the newspaper office I’d throw my first paper. So I have the best route in town with one exception, it was really hard to collect. It was harder for me to collect from the guys in the country club addition and out in the East Holdenville. But

it still was right there and that route built up just by those other two routes opening up next to me. So I ended up with 156 papers. I had the biggest route on the Holdenville Daily News at the end, which had great advantages. Your first out, that’s closest to the newspaper always, but because I was the largest, always they got those papers to the carrier first, because he was the biggest. My cousin had the farthest to go. He delivered out in the country club addition and he always walked. It would take him an hour to get to where he threw his first paper. When he threw his first paper, I was already finished. I’d be home at night for supper and he wouldn’t come in, sometimes it would be six o’clock and we would go ahead and eat. He wouldn’t come in until eight o’clock. It would be pitch dark when he showed up.

JE: And you were making more money too?

BP: Oh, I was making three times as much as he was, and that came up several times. That all I was interested in was making money. He would say that. Which I would say to him, “What are you interested in doing, walking two hours before you throw a paper?”

JE: Were you a money saver then?

BP: Oh man, yes. I drove my mother crazy. I saved money. We had a house it was 1,170 square feet. The reason I know that is because my wife, four years ago bought that house and moved it to the ranch. From Holdenville out to the Mesa Vista Ranch in Roberts County is 330 miles. So we measured it and we knew exactly how many square feet was. That was the largest house I lived in until I was married and had two children and my wife

was pregnant with our third child. All of my houses after that were smaller than the 1,170 square feet. But I hid the money in a closet. I had a crawl space underneath the house and I put a rug over it. My mother knew it (the crawlspace) was there but she never thought that that’s where I was hiding money. And I know she must have gone over my room 100 times trying to find how much money I had. And I would not tell her

and it just about drove her crazy. Because she knew I was saving money, she didn’t know

how much I had and she could never see me counting it or anything else. I kept it all outside. So finally I had to tell her, and I had like $242. That was big. That was big. But I remember also that Frank Crane had a jewelry store there in Holdenville. He was moving to Broadway where I started throwing papers on Broadway Street. And I used to throw papers right by Frank Crane’s and I became interested in a Bulova watch and it was $18.75. And somehow my grandmother, I probably said something in her presence and she said, “Now, tell me what are you thinking about doing?” And I said, “I want to buy a Bulova watch that costs $18.75.” And she said, “Well Sonny, that’s way too much watch for you.

You don’t need that much watch. Westclox you can get for $3 and then you’d have $15 to save. Well, I really liked this watch so I kept talking about it and she could tell that I was getting serious and they knew I had money. Don’t you step up to Frank Crane and pay

$18.75. She said, “Does he know you have money?” I said, “Yes, it was in my billfold and he has seen the money.” She said, “You tell him, you’ll give him $10 for that watch.” This is in the early 1940s, things were tight and all. And she said, “Let me tell you, you don’t know what money can do for you. Show him the money and then make him an offer.” I said, “I can’t do that. I can’t tell Mr. Crane that all they give him $10 for his watch.” She said, “Of course you can, practice on me.” She made me stand there and tell her that I was. It was humiliating that I had to act like she was Mr. Crane. And so, I finally bought the watch and I paid him $15 for it. But, I never did tell him I’d only give him $10. She said that cash is king in every discount in what you can do with cash.

JE: What great basic knowledge of money they were laying for your life.

BP: Absolutely. I mean it was an incredible experience. Every one of those times what they were telling me makes so much sense. It didn’t at the time, but it did later.

Chapter 6 – 6:25 Dust Bowl Days

John Erling: Who were the Kelker Street boys?

Boone Pickens: Oh, they were Bobby Loftis and his brother and Tommy Fancher and Ricky Sales and Orville Guess. We’d take anybody on any town for baseball, football or whatever.

JE: It’s remarkable that you can remember their names, all these years later. You never considered yourself poor, or rich or anything. I mean you were an average income family.

BP: You know, I’ve thought about that. Because people always said, “That was back in the Depression, what was it like in the Depression? Did you have plenty to eat and all?” I mentioned about the garden and so, you know, if you think about it we were making everything work. Nobody ever complained. At the table I can remember reports about

people moving to California. Because my aunt was a teacher, she knew. And my mother, she was head of OPA Office of Price Administration is what that stands for and what the rationing was called. She knew as well because people were apparently letting her know that they were leaving. They would talk about families moving to California because there was work out there. You know, kids would leave your class. And I can remember one girl moving in, her name was Ruth Herrod. And Ruthie was a really cute girl and I was immediately attracted to her. We were 13 years old. They moved in with the Herrod’s that had the dairy. I didn’t think anything about it, and she was there a little over a year.

And then they moved to California. And I was going out to make a speech out in Fresno, California about 10 years ago and she called me and said, “Do you remember Ruth Herrod?” And I said, “Sure.” She said, “You’re going to speak here in Fresno and that’s where I live.” So we’re talking and I said, “You were there just one school year.” And she said, “Well, you know what the deal was don’t you?” And I said, “No.” And she said, “Well we didn’t have any place to live. So we came to Holdenville to live with my dad’s brother.

We had two families living in a three-bedroom house. It was extremely tight there and

it wasn’t very long before people were very unhappy, because it was too close quarters. And my uncle told us that we had to find someplace else. So my dad found his place in California. So it was all over the fact that we didn’t have anything. It was a short stay in Holdenville and then we went to California.”

JE: Those were the dust bowl days.

BP: See that was going on and I must have been just protected because we had a very stable household. Everybody had a job. My grandmother had a big garden and she was contributing and she did the cooking. My aunts taught school. My mother worked for OPA. My dad had a job. So there was money there. I don’t ever remember somebody saying, “Well, we can’t do it.” One thing I would like to add is that they gave. They always

were generous. What do you mean generous, you didn’t have a lot of money? No, but you can still give. We were pretty close to the Rock Island Railroad line and guys would be on the train riding the rails. They always called them bums. The train stopped there and they would get off and they were hungry and they would come up the street. My grandmother would feed them, but they had to work until the food was ready. She said, “It’s going to take me a few minutes. Now you can rake that out there or you can haul that over there or you can carry the laundry out to the line, or something.” But she didn’t want them just standing around. And then, she finally figured out that her house was marked somehow. Somebody had put a mark somewhere. That was discussed. I can remember that. Our remember my dad said, “Ms. Molonson, do you want your house marked so that these bums come from the railroad?” She said, “They’re hungry.” She would feed them. She had a red cross, just a red cross on a card. You may remember them. They used to put them

in the front window. It didn’t say “Red Cross” on it. It just had a red cross on there. And I remember asking her one time I said, “Why are you the only person on the block that has that red cross in the window?” She said, “I’m the only one that gave.”

JE: That’s great. The first elementary school you attended, what was it?

BP: It’s interesting because I saw a picture of it last week. I didn’t even know the picture existed. I was going through a box of things and came across it and it said fourth grade. Somebody asked if I could pick myself out of the picture. And I said, “No, because I’m not in the picture.” And they said, “You’re not in the picture? What do you mean? Didn’t you go to school here?” And I said, “Yes, it’s Central grade school, it’s over on East Main.” They said, “Well it says fourth-grade there, you’re not in the fourth grade?” And I said, “That’s my mother’s class.” It was my mother’s class. And there was a check above a child that was kind of in the middle of the picture. And see, she’s short, and there’s a little check on top of her head. And we went back through and they had all the names written out on the back. We went across and read the names and figured out that the check on the other side was my mother. I just couldn’t see her because she wasn’t tall enough to get in the picture. And so it’s just the top of her head. But it’s interesting though when

I saw that picture, Central grade school it was a two-story building and it burned down. It would’ve been a fabulous building to always have because it was really a spectacular school, and then it burned down.

JE: Do you remember any teachers from back then and were you a good student? Were you interested in your studies?

BP: Yes. Ms. Mackey and Ms. Rushing, all of them I remember them. They all had a part of my life. And somebody asked me over at Oklahoma State University, they said, “You know you’re so interested in sports and everything else.” And I said, “Let me just take you back. I can tell you who my first grade teacher was, Ms. Rushing. I can tell you stories about Ms. Rushing.” Then I went to Christine Mackey, and Christine Province and Mary Leach and all of them had a part and I remember them very well as teachers.

JE: What was your first job in the oil business?

BP: I was a roughneck. I was 16 years old working for a living.

JE: Did you pump gas at a gas station?

BP: Oh I did, but I didn’t consider that to be a job in the oilfield. I worked for Ray Smith at the Sinclair station over on Hinckley Street in Holdenville. I could work here almost any time I wanted to because I was a good worker. And so if he needed any help and I was around I would go by there and he’d say, “Yes, park your bicycle and come on in here and help me out.” I was a pretty good tire buster. I could fix flats pretty well.

Chapter 7 – 5:48 Henry Iba

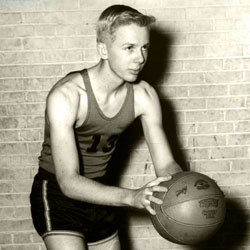

John Erling: In high school, you were active socially, you played basketball, talk about that. You graduated in what year? 1946?

Boone Pickens: I was supposed to and I stayed over an extra year. See, I moved from Holdenville in 1944. I think things were tougher for us then, than at any other time. And my dad had gone to work for Ford Bacon & Davis in Little Rock, Arkansas. He would come home once a month. And my mother was with OPA. And then in 1944 I think OPA was winding down and my dad got a job with Phillips Petroleum in Amarillo. So, he went up there in 1943, and he was out there year. Then my mother and I moved out there

in August of 1944. So I attended my sophomore year at Holdenville High School and I played on the basketball team. So when I moved to Amarillo, that was in a period where if you had ever played in another high school, then when you came in, you had to sit out a year. And, that all came from the fact that they recruited from high schools at that time. Amarillo was notorious for recruiting from out of western Oklahoma. Now, I wasn’t from western Oklahoma, I was from eastern Oklahoma, but nonetheless I was from Oklahoma. So when you came in there you are ineligible, so I sat out that year. We had a coach that could see the opportunity of a great high school basketball team, but there were two kinds of players. I was ineligible and then there were two other guys that were young

and they were playing on the sophomore team and one of them was an exceptional basketball player. So the coach put together guys that stayed over an extra year, which you could do if your birthday was before June 1. He mapped all that out, and our team, five guys, actually three of us should have graduated in 1946 and two of them were legitimate sophomores. We hadn’t done anything dishonest. I mean you could do this back then and a lot of schools did it. So I did stay that extra year and graduated in 1947. So when I went to college I was 19 instead of 18.

JE: I think it was in 1927 a major oil field was discovered in Seminole, not far from Holdenville. And then that ran its course through 1938. That was good for your dad, but then when it ran its course, he kind of ran out of luck?

BP: Yes, he had gotten into the business as an independent. I kind of got ahead of myself. He went to work for Phillips in 1943. But in 1938 that was about it for him. He couldn’t get casing for one thing, and now we’re getting ready to go into the war. He just ran out of money too. And so he went to work for Ford Bacon & Davis in Little Rock, Arkansas.

JE: When he ran out of his luck, did that affect your family in some ways?

BP: It was sad.

JE: You definitely remember that?

BP: Oh yes. Because he wasn’t home, he would just come home once a month. He would be there three days and then go back to Little Rock.

JE: So when we come up to December 7, 1941, do you remember that day, Pearl Harbor?

BP: I remember it very well. I was sick and it was the biggest day for a paperboy that you could imagine because they were getting the Extra-Extra edition out for delivery. And I finally talked my mother into letting me go. I had a cold and a sore throat and everything else, but we were getting 25 cents a paper, so it was a fabulous opportunity to sell newspapers. They had cars and you would ride down the front of the car and go down the street and yell, “Extra! Extra!” And people would come out and buy a paper. Well you know, if you sold 20 papers, you made five dollars. That was a big deal.

JE: Then your dad went to work for Phillips Petroleum Company in Amarillo?

BP: Yes.

JE: And you played basketball in Amarillo high school?

BP: Yes, that was the team that I went out there and then I stayed over until 1947 and played two years as a senior. We went to the state tournament in 1946 and we got beat in the quarterfinals. And then we went in 1947 and got beat in the finals.

JE: You played as a guard?

BP: Yes.

JE: Then you got a scholarship out of high school to Texas A&M?

BP: Yes.

JE: How did that work out for you?

BP: All scholarships back then were for one year, so they had to re-up for the next year. And they told me they were not going to renew me for the second year, so then I transferred to Oklahoma A&M.

JE: That would’ve been in 19–

BP: 1948.

JE: Didn’t you walk there and play?

BP: I had tried out for them in the summer of 1947, so Mr. Iba knew me, but they didn’t give me a scholarship then. So I contacted him and he said, “Boone, if you want to come out, sure walk on, we’ll have you.” So I did go up and go out for basketball.

JE: What kind of the guy was Henry Iba?

BP: He was a very serious man. He was serious because he wanted to win and he expected to win. You knew what it was all about pretty quickly. He was going to win and you were going to be a part of it if you wanted to be. But if you didn’t want to be a part of it, you would get eliminated very quickly. You never called him anything but Mr. Iba. People say, “Coach Iba” but nobody I ever heard called him Coach. They called him Mr. Iba. Gene Smithson was the assistant coach. When I transferred from Texas A&M I moved from the

Southwest conference. We actually had a really good freshman team and we beat Texas both at College Station and Austin that year. The freshman team did. So I transferred up there. I stayed out and was ineligible that year. So one more time I was going to sit out a year and so that meant you just played defense all the time. And I guarded every once in a while, not often, usually they had me guard in practice Norman Pilgrim, who was very quick and very good and all. But sometimes I guarded the player from Enid Don Haskins that later coached the team that won the NCAA in 1964. He was at UTEP, they beat the University of Kentucky that year, there’s a show about it.

Chapter 8 – 6:21 key Moment

John Erling: Your staff provided me with this book. I can’t help but read this headline that was in the Holdenville newspaper about 1932. “Boone Pickens, 4, is Holdenville’s First Volunteer in Case the United States is Forced to Take Up Arms in the Far East.” And then there is a story that follows it. “Holdenville’s first volunteer to join Uncle Sam in the event the United States becomes actively involved in the Sino-Japanese trouble is none other than Master Boone Pickens, four-year-old son of Mr. and Mrs. Tom B. Pickens of 217 N. Kelker. So tell me the story behind that.

Boone Pickens: I don’t know. I mean at four years old I don’t remember the story. But I remember I had seen that in the book though, it was in the paper

JE: That’s cute. You went to school, transferred to Oklahoma A&M which would later become Oklahoma State University. A key moment in your life was when your father told you, you should switch majors. What was your major at the time?

BP: Well, my major at the time was business. But what I had done, this was when I was initiated into the fraternity SAE and my father was an SAE and he came over and pinned me. That was in February of 1949. He came over with his pin and pinned it on me. I was initiated into the fraternity that Sunday. And we walked out into the lawn at the fraternity house on 3rdStreet I believe. He said, “I have something else I want to talk to you about. You are not on the same schedule that your mother and I are on for you to graduate. You went to Texas A&M in pre-veterinary medicine and that didn’t work. And now you’re here in Stillwater and you’re in business, and I’m not much into getting a business degree. You need to get into either engineering or geology and get the hell out of college. And that, for us is going to be June of 1951.” I said, “Well, I don’t know whether I can switch over to geology or engineering and to do it.” And he said, “Well you’d better figure it out, figure out a way to do it.” And I said, “I’m getting the picture that you are serious.” And he said,

“Listen son, a fool with a plan can beat a genius with no plan. And your mother and I have a concern that we have a fool with no plan. So you’re getting ready to get a plan and get out of school and that’s it. I said, “Okay, I sure appreciate you coming over and pinning me. Part of the day was a real nice day.” And he said, “There’s nothing wrong with the other part of the day, just get it done.” I switched over to geology and got out of school in June of 1951 I carried for two semesters 18 hours, and one semester of 19 hours and went to summer school for one summer and I got out.

JE: He chose geology for you because of his experience in the oil business?

BP: Well I went over to see Dr. Lowman who is the dean of engineering and he looked at my transcript and he said, “When did you say you had to get out?” And I said, “1951.” And he said, “Pickens I don’t care how smart you are or how hard you work you couldn’t

get out of here until 1954.” So I went down the street to Dr. Monett and he looked at my transcript and he said, “You know if you carry two 18-hour semesters and a 19-hour semester and go to summer school you can do it.” And I did.

JE: Wow.

BP: When I graduated, my dad said, “I’ve got one more thing for you.” And I thought he was getting give me some cash. Now I’m married and I have a child in right after graduation and going to go to Bartlesville. I said, “Okay dad what is it?” He stuck out his hand and said, “Good luck.” No money just good luck, which that’s all I needed.

JE: You went to work for Phillips Petroleum in 1951 in Bartlesville. You gave that a couple of years and didn’t really care for the bureaucracy I guess?

BP: No, it was more than that. I was in Bartlesville for really two months and then they told me I wouldn’t be there but just shortly and then they would send me to a district office. So they sent me to Corpus Christi, Texas. I worked in Corpus for two years and then they transferred me to Amarillo and I worked there for a year. And then I left in November of 1954, so I was there for 3 1/2 years.

JE: Were any of the Phillips family around back then?

BP: None of the Phillips, but I met Boots Adams in kind of an interesting way.

JE: Yes, how was that?

BP: I was carrying some maps, and I had them thrown over my shoulder. They were linen maps that had lost the body to the linen and they were just kind of limp across my back. And I got on the elevator and he was on the elevator and he said, “Young man, hand me those maps.” And I handed them to him. And he said, “Put your arms like this.” And he put the maps across my arms. He said, “Don’t let me ever see you carrying maps any other way than this. Do you understand me?” And I said, “Yes sir.” And he said, “Do you know who I am?” And I said, “Yes sir, you are Mr. Adams.” He said, “That’s good.” The elevator door opened and he got off. And I never did carry maps to Bartlesville any other way than that way.

JE: And Boots Adams was the CEO then, the head of Phillips at that time?

BP: Yes he was the CEO.

JE: So you leave Phillips Petroleum and then you go out on your own? You live out of your station wagon, prospecting–

BP: Well, I had a home in Amarillo. I had a wife and two children and my wife was pregnant with our third child. That was the house that was larger than the Holdenville house. It was 1,625 square feet. But I was working out of my station wagon and I was doing well- site work, so I was sleeping in the back of it. I had a sleeping bag and it was winter so I crawled in my sleeping bag and worked out of there. It worked pretty well, no problem. I had prospects and I was buying leases from time to time.

JE: And then you formed your first oil company?

BP: That came up in September of 1956.

JE: Petroleum Exploration Inc.

BP: Yes.

JE: Tell us how you grew that company.

BP: Well, I raised money. I didn’t have any money so I raised money and people participated in wells with me. I had drilling funds and actually I raised drilling funds four times. They were for $500,000 apiece. And with drill wells I got good results. Then two guys, John O’Brien and Gene McCart said, “Look, you need more money because you’re spending too much time raising money so we’ll give you a line of credit, not any money but a line of credit.” They gave me a $100,000 line of credit. And said, “Now you could buy your leases and everything else from the bank.” And they guaranteed the loan. They got half the company and I got half company. It was a very good deal for both of us.

JE: And you were about how old at that time?

BP: Well, it was in September of 1956, so I was 28 years old.

JE: A young man. You had to establish yourself and you had a trust factor about you that made them want to invest in your company?

BP: I did and it was a good investment too. They made a lot of money out of it.

Chapter 9 – 6:28 Take Over

John Erling: So then comes along Mesa Petroleum in 1956?

Boone Pickens: It was Petroleum Exploration Inc. and then we went public in 1964 and that’s when Petroleum Exploration–and we had a Canadian company called Altair Oil and Gas and those were put together and that became Mesa Petroleum.

JE: Mesa then becomes the largest independently owned oil and gas company in the United States?

BP: It did become a large independent. I’ve forgotten now, who it was who used to challenge me on whether or not they were larger than we were. But, anyway it was a big

independent and we ended up drilling around the world. In Africa and we had production in the North Sea. We had 54 platforms in the Gulf of Mexico. We became a big company.

JE: You must have thought could life get any better than this?

BP: Oh I don’t know. I thought it could get bigger and better. I was struggling with finding oil and gas cheap enough to continue to run a big exploration program which had gotten up to $500 million a year, which was big at that time. That’s not so big now. Then I decided to go for acquisitions and that was in the early 1980s.

JE: And then the acquisition was Hugoton?

BP: Hugoton was the first one. That was in 1969. We acquired Hugoton. It was 20 times our size. Then we were busy in the 1970s exploring and we were successful. We found a good field in the North Sea and we found production off the west coast of Australia and came really close off the coast of Carbon in Africa. We hadn’t found but they changed the deal on this and I didn’t like the change in the deal so we didn’t pursue that any further. But we had good exploration people. Most of them came out of Shell petroleum and they were well-trained people.

JE: Then Hugoton and Mesa then merged?

BP: Yes, that’s right. We actually acquired them, we were the survivor.

JE: Right. But you weren’t satisfied with this success of Mesa then and is that’s when you started thinking of a takeover aspect of an oil company and your first target was

City Service?

BP: City Service and General American then came Gulf and Phillips and then Unocal.

JE: City Service was number 38 on the Fortune 500 list in 1982. When you went into this to people laugh? Did they think who in the world do you think you are? Or ask how do you think you can do this?

BP: All of that. But they did look back on that Hugoton deal, they were 20 times our size.

Actually what happened with City Service, we were after them and they turned around and went after us. Then Gulf bought City Service and then they had problems, City Service and Gulf did. We got clear out–we were gone. And then they had lawsuits in the deal and they weren’t resolved for 20 years. City Service then ended up going to Occidental Petroleum.

JE: But you were able to pocket some coins as a result of that?

BP: We made money out of all of it.

JE: $32 million dollars.

BP: That was a lot of money then. It wasn’t anything like the one coming up.

JE: Then you set your sights on Gulf Oil, Phillips Petroleum, Unocal and during this time you lead a successful acquisitions and pioneer in the mid-continent assets of Conoco. Back to Gulf for a minute, Gulf hired detectives to dig up dirt on you.

BP: All of them did, not just Gulf. But Phillips and Unocal they all had detectives on me.

JE: Did you even see them sitting outside your house?

BP: No, it wasn’t my house, but in Boston my wife noticed it. We had somebody in the lobby of the hotel that was really interested in me checking in. We went back down and went to dinner and when we did, well the same guy was there. And then when we went to dinner at Locke-Ober in Boston and when I got up and went to the men’s room the guy was sitting at the bar. So I went over to him and I said, “Now hey look, you’re interested in me and now I’m getting interested in you. Why don’t you just come and join us for dinner?” He said, “I don’t know what you’re talking about.” I said, “Sure you know what I’m talking about. Whom do you work for?” He said, “I’m not going to tell you anything.” And he walked out. So they changed and we didn’t see him again, they got another guy.

JE: You were called many names, you were called a Green Mailer what’s a Green Mailer?

BP: Oh it’s where you run up the stock. You buy a lot of stock in a company and run up the price of stock in an offer and then you sell out. I never did that. I had one guy on CNBC that called me a Green Mailer and I got him on TV five years later and I said, “Now I’ve got you in front of the camera, tell me where I’ve ever green mailed anybody.” And he said, “You didn’t. I was wrong about it.” And I said, “Good, thank you. That clears that up.” No, I never green mailed anybody.

JE: They even called you a communist?

BP: That probably was Fred Hartley he called me a son of a bitch, a communist and whatever else was on his mind.

JE: A piranha?

BP: Oh yeah.

JE: Were you ever physically threatened?

BP: No, I never was.

JE: How to do live with this controversy? How did it affect you? Did it depress you? Did it just fall off your back?

BP: Well one thing about it is you see, I believe shareholders own the company and managers are employees. That’s the way I always considered myself. Even though I was the founder of Mesa, I still was an employee. I was also a shareholder, so I was an owner too. But I never ran the company like it was my personal fiefdom. I did a good job for shareholders.

I even got in trouble over distribution to shareholders. It was a bad call on my part. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, I distributed, I said I did but really we did–we distributed

about $200 million to the shareholders. That was okay except the gas price went down and caught me with $1,000,200,000 worth of debt. That was kind of the windup of my story, so we sold out.

JE: On the cover of Time magazine titled The Takeover Game, Corporate Raider T. Boone Pickens. You were there, you were shown holding cards and there were oil derricks on the back of the cards. And you say the cover actually missed the point?

BP: Yes. I was working on behalf of shareholders. And of the companies that I caused to either sell out or be taken over in some way or another, over $1 billion enhanced value of those companies I feel like I caused. Shareholders loved me. If I showed up they were happy. It’s management that didn’t like me. And management had control of the PR angle to the whole thing and the business roundtable raised money, about $10 million, to do everything they could to ruin my reputation. But it was okay. I mean it was a hard ball game and I felt like we didn’t win every contest, but we made money out of it. The biggest deal we made was the Gulf Oil deal and we made $500 million out of it.

Chapter 10 – 3:59 Turn Around

John Erling: And then there was a turnaround because Mesa then became a target of the takeover by David Bachelder.

Boone Pickens: That’s right. That was in 1995. David is an OSU grad. We are fraternity brothers.

JE: And one of the biggest surprises of your life?

BP: It has to be the biggest surprise.

JE: That deal fell through.

BP: Hell, we beat him. I never could figure out why David did it and finally I think what it came down to is it had developed over a long period of time. But, David anytime I was ever in any contest with him whether it was gin rummy or racquetball, he never won. Now did he win some hands? Of course he did. Did he beat me on some games? Yes, but who one? I won. And I think that drove old David crazy. He just hated it because he really never did beat me.

JE: Wasn’t there a time about 1996 when your stock had dropped to $2 5/8 a share?

BP: Yes.

JE: And the question was should we take Mesa into bankruptcy?

BP: That was discussed, but we didn’t do it of course.

JE: How do you avoid getting down on yourself?

BP: Well, you cut your throat when you did it because you have distributed $1,200,000,000 to shareholders and right at that point your company had gone down in value

tremendously. All you needed was $300 million to recapitalize the company. So if you hadn’t made one of those last distributions to shareholders you’d have had the money to recapitalize yourself. So yes, you hated the outcome. You didn’t like it, but it was time to make the deal. And you didn’t like the deal, but you made it and moved on with your life.

JE: So then Mesa was all right and you left it then after 40 years?

BP: Yes, they merged Mesa with Parker & Parsley. I stepped down in September of 1996, which if you go back to when we started, not went public, but we started in September 1956. So it was 40 years there. Six months later they merged Mesa into Parker & Parsley and I stayed on the Board and then got off and was out of there. The company now is called Pioneer Natural Resources.

JE: This is worth noticing, you were involved in the creation of the United Shareholders Association from 1986 to 1993 and that was attempted to influence the governance of large companies.

BP: It was to give the companies back to the owners, which were the shareholders.

JE: It was widely held that you made American business more competitive by doing that.

BP: I think that’s exactly right. And I was totally vindicated. As the outcome over the next 20 years revealed it was clear that I did have an influence on it and it was a good influence.

JE: You must have walked in a number of boardrooms where CEOs in there just hated you and wouldn’t talk to you. You might have walked into them and said, “Hello.” And they would ignore you?

BP: No, nobody ever ignored me but there were guys, you know I’d see them at Augusta National at the Jamboree down there. I was a member and they were members, and they weren’t friendly with me. But, you know, so what? Were you on the right side of the issue? You were. You were on the right side of the issue. So, if that’s the case you just keep driving until you hear glass breaking. Don’t worry about it. Just keep checking your position and as long as you’re comfortable that what you’re doing is the right thing, well just go ahead and keep doing it.

JE: You’ve had a certain sense haven’t you? A natural sense of which is the right side apparently. Is it a gut instinct?

BP: I had a guy say one time say, “I’ll tell you one thing, I’ve never caught you on the wrong side of a question. You’re always on the right side of the issue.” And I said, “Do you really believe that?” And he said, “I do believe it. I also believe that if you aren’t on the right side of the issue and you understand it you will change.” And I said, “You’re exactly right.” That’s the way I felt about myself. I think I analyze well and I have not always been where I’d like to be, but when I’m not, I will go ahead and change and say, “That’s a mistake. I’ve made a mistake.” It’s a lot easier for me to clear it up that way then to hang in to the bad side and get roughed up and keep trying to explain something that’s hard to explain. Just

go ahead and say, “Hey, I made a mistake.” People make mistakes, everybody does. And if you make as many decisions as I do you are going to make some bad ones.

Chapter 11 – 4:55 Pickens Plan

John Erling: But I think America agrees with you on the decision you’ve made on the Pickens Plan. And you say America is addicted to foreign oil. Just talk to us. Here we are in 2010, how addicted are we?

Boone Pickens: You are the most addicted country in the world. How do you like that? You are buying five million barrels of oil a day from the enemy. You are paying for both sides of the war. That starts to border on being stupid. You are importing 67% of your oil. Now, your oil imported from Canada and Mexico and some other friendly places around are okay, but you are importing 13 million a day and you are using 20 million a day. So here you are and no other country has this profile. No other country. That’s part of the credibility problem for America globally. We are so addicted to oil that we are buying it from the enemy.

Other countries don’t understand that, they think we’re crazy. Because we have resources in America and we just haven’t had the will, the resolve and the leadership to go and develop our own resources and use those and get off the oil purchased from the mid- east. OPEC oil is what we don’t need to be buying. So here you are, you’ve got in barrels of oil equivalent to natural gas 700 billion barrels. That’s three times the reserves of the Saudi’s in oil. You’re just fine. All you need is leadership, which we haven’t had. President Nixon in 1970 said that at the end of the decade we will not import any oil to the United States. At the point he made that statement we were importing 24%. At the end of the decade it was 28%. Now who is to blame? Is it Nixon? Not totally. The others that you now can blame are the media. Why didn’t they hold him to it? Why didn’t they say, “Look you told us we would not be importing any oil.” Now you go from Nixon forward. If you have challenged Nixon at that point you would put other candidates and then presidents of the United States on notice, you will be challenged on remarks that you make about energy.

Going forward from that point, every person that ran for president of the United States, those that were elected, it doesn’t make a difference whether they were Democrats or Republicans said, “Elect me and we will be energy independent.” Like it was just going to be something that would happen automatically. And nobody was ever challenged. That did not happen until I finally got up in June of 2008 and I woke my wife up in the night and I said I’ve made a decision and she said, “What is it?” I said, “Somebody has got to tell the American people about the security issue of our continuing to import oil from our

enemy.” She said, “And I know that you’ll do it and you’ll do a good job. Now let’s go back to sleep and do it tomorrow.” (Laughter) In July 2008 I launched Pickens Plan, which July 8 is my mother’s birthday. And we explained the problem and I spent $62 million doing it. Did I get my money’s worth? I think so but that’ll all be decided whether I got my money’s worth by the end of this year, because we’re either going to have an energy plan for America or we’re not. Now you say if you don’t have it this year you could have it next year. If that’s the case you still could be proven correct. That’s right. But I said we’d have it by the end of 2010 and I still believe that’s going to happen.

JE: And for the record it’s a plan that promotes oil alternatives such as natural gas, wind power and solar energy.

BP: Also the battery. Anything American I am for. Anything. I’m for ethanol. I’m for anything that’s American. I want off the OPEC oil.

JE: Right now I believe the primary focus of yours is to convert large trucks to use liquefied natural gas as their fuel with a government subsidy for conversion?

BP: There are 8 million 18-wheelers in the United States. So target on that and it will show you what you can do very quickly. If you move the 8 million over to natural gas, now know this, the only gasoline ethanol battery will not move (power) an 18-wheeler. So this leaves it up to natural gas. It’s 30% cleaner. One MCF of natural gas is equal to 7 gallons of diesel. So the cost of one MCF of natural gas is four dollars and the diesel cost is $20. So it’s infinitely cheaper, it’s 30% cleaner is it’s ours and it’s abundant. If we do not capitalize on this opportunity we will go down as the dumbest crowd that ever came to town. I mean we are real saps if we let this opportunity get away from us.

JE: Do you sometimes feel like a lone wolf out there?

BP: A little bit but I’ve felt like a lone wolf before. It’s not a role that I’m uncomfortable with.

JE: Right, you felt like an underdog way back when.

BP: Yes. Somebody called me a gunslinger. Yes, I travel light and travel far and try to get some things accomplished. If you want to hook up with me, I’d love to have you. If you don’t, I’ll go it by myself.

Chapter 12 – 5:00 John kerry

John Erling: You have had criticism all along here because you are seen as trying to solve the energy crisis, but then some critics say you’re trying to gain financially at the same time? Boone Pickens: If I wanted to do something financially I would’ve never spent the $62 million.

That would be a good place to start. (Laughter)

JE: Right.

BP: No, but does my portfolio have gas stocks in it? Yes it does. I’m for anything American. I mean it’s very clear. You can come at me however you want to. But we better get an energy plan or we’re going to find ourselves in tough shape from a security standpoint.

JE: You find yourself with strange bedfellows even now with Al Gore.

BP: Al and I get along okay. Listen, I got out of politics. That’s the only place Al and I are going to have any problems. I mean he wants to get green. He was not aware that the 18-wheelers would not move on a battery when we talked about it. And we had lunch

and he said, “I’ll come out for 18-wheelers on natural gas if you’ll go the battery light duty.” I said, “That’s fine with me. I’ll go the battery light duty.” Listen my program is very, very simple. And if the president of the United States will do what he said he would do, and that was when he accepted the nomination in the summer of 2008. He said in 10 years we will not import any oil from the Mid-east. Okay, now let’s have the plan. Two years have passed and we have no plan. All right, now this is his plan I think. He needs to give an executive order that says all federal vehicles in the future will be on the domestic fuel. I don’t care what it is, just so it’s domestic. Secondly, said that he needs the 10-year target that he gave us. He says the American people in the next eight years will decide to move to a domestic fuel for their own transportation fuel. So you’ll pick a battery or you’ll pick a hybrid or you’ll pick ethanol. You’ll pick natural gas. You’ll pick something, just so it’s domestic. Now I can tell you I’ve had 38 town hall meetings and I am in touch with the grassroots of America. When I ask them, how would you feel if you were challenged to pick a domestic fuel and get off of OPEC oil in the next eight years? And I can tell you

it’s 100%, all of the people raise their hands and say I can do that for America. And we’re going to get it done. It’s going to happen.

JE: Do you really see this president making that happen?

BP: If he doesn’t, somebody else will. Because we cannot continue like we are. If we continue, what’s going to happen to us, Mexico will be a net importer instead of an exporter. So that loses 1,300,000 barrels a day for us. Venezuela can’t wait to get their oil to the Chinese, but they owe the Chinese $20 billion so it has to go there. The Chinese are building a refinery that will process their heavy crude and that’s gone from us. That’s 1,200,000 barrels a day. So between Mexico and Venezuela in three years, that’s 2 and a half million barrels of oil. If we don’t do something about it, where we go for the two and half million? Back to OPEC. Then we will be at 7 1/2 million barrels a day. If that is the case, if we go 10 years and do not do anything more than we’ve done in the last 40 years,

we will be paying $300 or $400 a barrel for the oil and we will be importing 75% of our oil.

JE: You’ve met a good number of our presidents going back to Nixon would it be or further back?

BP: Further back than that.

JE: How far back?

BP: Well, I knew Johnson. Johnson would be the first president I met.

JE: So all of those coming back through now. You were a big supporter of George W. Bush, and his father too I would imagine?

BP: Yes.

JE: How do they all stand? Anything unusual?

BP: I’ll tell you how it stands. Not a one of them ever did anything for energy for America.

They never really understood it. They never understood it. They just kept importing more oil from the mid-east. They think those people are friends of ours. I don’t.

JE: They didn’t understand it but it seems to be such a simple concept. It’s going to take a lot of leadership to make it happen, and they didn’t have the energy to do it?

BP: I don’t know. But it didn’t happen, I can tell you that.

JE: Did you ever stay in the White House?

BP: No, I never have. I’ll tell you who understands quite a bit about energy. Clinton.

JE: So then what did he do in his administration?

BP: Nothing. He tried to though.

JE: Do you think he probably tried to do more than many of the presidents?

BP: Yes, I do.

JE: And he couldn’t make it happen?

BP: No, but now you can because you’ve got such an abundance of natural gas. That’s the key to it.

JE: It’s interesting that you and John Kerry are now on an energy bill.

BP: We were, but they have dropped the climate part of that bill off. We couldn’t get the votes. Now my stuff still holds up.

JE: And for the record, obviously you questioned his Vietnam service?

BP: That was 2004 and we’re going forward from there. Kerry and I are working together. He’s working for America and I am too and it has nothing to do with politics.

JE: And I only pointed that out to show how the two of you have now come together focusing on the same subject and basically do agree.

BP: That’s right, we do agree.

JE: There was a time that you were going to run for president wasn’t there? How serious was it?

BP: Oh, not very serious. I was going to run for governor and I was serious about that, but I didn’t do it. As you know, I think it was a good call on my part. That was in 1992 and I decided I didn’t want to do it.

Chapter 13 – 4:12 Do not Cheat

John Erling: By my research accounts you’ve given more than $700 million to charity?

Boone Pickens: Over $800 million.

JE: Okay. OSU, relief efforts for Hurricane Katrina, the University of Texas, programs for the well-being of families, children, teenagers and animals and just a few days ago you joined 40 other wealthy men and women in giving at least half of your wealth to charitable organizations.

BP: I’m on record I think it was 1983 or 1984 in Fortune magazine, saying that 90% of my net worth would go to charity.

JE: So you were already there, more than there.

BP: That’s what I told Bill Gates. I said, “I have already said I would do 90%.” He said, “Will you do 50% with us?” I said, “Sure, I’ll be glad to.”

JE: And so Bill and Melinda Gates have solicited the pledges known as The Giving Pledge. Was there a secret dinner where everybody gets these 40 wealthy people together? Or did they just contact you on the phone and ask for your support?

BP: I was talking to him about energy and he asked me to do it and so we’re trying to understand the energy question together and he asked me and I said, “Sure I’ll be glad to.” So it was a brief telephone conversation.

JE: You’ve given nearly $500 million to OSU.

BP: It will be between $400 and $500 million.

JE: We have seen Pickens Stadium and obviously you want the whole school to be competitive in athletics and academics. Are they coming there to that point now, say, in football?

BP: We’ve got a long way to go. In football I don’t think we are competitive to the level that I want to see us. But you know, if Boise State can elevate, Oklahoma State can too. I’m not happy with the fact that we haven’t beat Texas or Oklahoma in the last five years.

JE: The academics have criticized you for giving so much to athletics.

BP: Oh listen, they had better be careful on that. I’ve helped the academic side there. I’ve generated probably with my funds and matching funds and everything else over $300 million that’s gone directly to the academic side in particular to professorships and chairs to the faculty. No, I’ve received nice letters from the faculty on that. If somebody’s complaining about that recently I’d be really surprised.

JE: At first they did and I haven’t heard anything recently. But isn’t it interesting though that particularly with football that does become kind of a selling point to the nation about your school.

BP: There’s no question it does. NCAA football is huge in America. There’s no question if

you win, you want to win honestly, don’t ever drift from the honest approach to winning. I made that real clear to them. I said, “Fellas, you start cheating and I can tell you you’re going to lose your most enthusiastic supporter very, very fast. It won’t take but a minute if I am convinced you are cheating.” They know that. The staff. I get along well with Gundy and the rest of the coaches and everything and they know I want to win. Myles Brand who was the head of NCAA, he told me one time, he said, “If more big supporters

would do what you do, tell the football coaches that if you cheat, you’ll lose me.” He said, “I can tell you a lot of it would clear up real quick.” There’s nothing hazy about how I feel or what I say. Everybody, if they want to know they can just ask me the question.

JE: Have you said I am, or am not on the five-year plan? You are 82 now, haven’t you talked about that?

BP: Five years is too long for me to have a plan. I’ve had a five-year plan at Oklahoma State and we are through the five years, so I want to see results.

JE: What known individuals from the past, presidents, oil people or people from other fields do you admire?

BP: Ronald Reagan number one. I mean he was a real president. People said, “Did you have meetings with him?” I’ve had some meetings with him. They say, “Did you influence him?” No, I did not. I’m not kidding you. To me he had two traits that I admired so much. One of them was that anybody that heard him speak said, “That’s a sincere, honest man.” And I may not agree with him, (Reagan) but he’s approachable. And if I had 15 minutes with him, I think I could change his mind. He’s a nice man and he’s very polite. Could you change his mind? No. Any time I ever tried to change his mind I got nowhere. But, I’ll tell you what, he was right often enough that he was better than any president that I’ve ever voted for.

JE: You’ve contributed to the Ronald Reagan Library. I saw pictures on the wall of you with Nancy. She was very appreciative to you of what you did for them.

BP: I’m on the board of trustees there.

Chapter 14 – 3:58 Advice to students

John Erling: Advice for young students in the energy world or any endeavor. They’re listening to your story here. Do you have any advice for them?

Boone Pickens: Young student?

JE: Yeah.

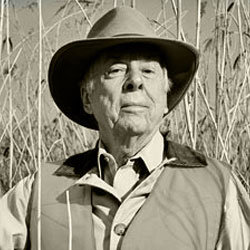

BP: Lucky you! Lucky you. Let me tell you, I’ll trade with you tomorrow. My ranch, my airplane, my bank account for your spot wherever you are, whether it’s Holdenville, Ada, Claremore

or anyplace else. I’ll trade with you. We can’t do it. We know that. But you have what I’d like to have, is, an opportunity to go forward, do all the things I’ve done. You can do bigger things than I’ve done. You just need to work hard, commit to it, enjoy doing it, don’t get stuck in a place where you’re unhappy. Listen, every job I’ve ever had, I’ve enjoyed it. I’ve never lived any place I didn’t like the place I lived. Just have the right attitude to move forward. What you have in front of you is much, much more than what I have.

JE: That says a lot. What are you most proud of as you look back?

BP: You know, I think that I’ve helped a lot of people. I get letters everyday that thank me for what I’ve done. And that’s good, I like that. I don’t know, it’s been a pretty interesting

life. Holdenville was a great place to grow up. I had the right kind of direction; leadership there—it couldn’t have been better. I got instilled with a work ethic that is active today. I went from there to Amarillo and graduated from high school there, went on to Oklahoma State. It’s just been an unbelievable life for a kid from eastern Oklahoma.

JE: What has becoming wealthy taught you?

BP: There’s a lot of responsibilities that go with it, I’ll say that. I’m not much of a shopper, and sometimes if I spend too much, I feel guilty about it. That all comes from my mother’s side of the family. It’s just been a great life. But I’m not through. I’m 82, I’ve got a lot of things left to do. I’m in a hurry—I know I’m not going to be here. Can see the finish line?

I hope not. I know it’s not very far out there. I’ll get some things done. And I’m gonna change some things.

JE: And so you’re day might start what time in the morning?

BP: Five-thirty. That’s when I get up. And then I talk to the office the first time at 6:15. My trainer is there at 6:30, and we start to work at 6:30, quarter to seven and work for an hour and I’m in the office by 8 o’clock.

JE: And you’ll go ‘til …

BP: It doesn’t make an difference ‘cause I like to work! Somebody says, “Gah, aren’t you tired?” Yeah, sometimes I get tired, but, “What do you like to do more than anything else?” Work. I like to make money. I like to give money away, I want to be generous with it. I have been. I’ve got a lot more to do. I have exciting days. Everyday’s fun. Today the market was lousy, but …

JE: Okay, we’re August 6th, 2010. What drove the market down today?

BP: The oil was down. The gas was down. The equities are all down. Everything was down. It’s just one of those days … I don’t know what did it. You had that bad unemployment deal that came in a lot higher than they thought it was going to. That had some influence. I don’t know. Tomorrow will be a better day.

JE: Well, Boone, thank you for this that you contributed to this. Your voice now is preserved forever and students that aren’t even been thought of are going to be born 50 years from

now can listen to your voice and I think that’s very important.

BP: I appreciate it, too, ‘cause I think that I have something to say. I’ve got accomplishments that are worth noting, so I’m glad I’m included. You know, this is Oklahoma, and I’m from Oklahoma.

JE: We should say you have your book …

BP: Well, the first book was in ‘87 was Boone and the second book was The First Billion is the Hardest.

JE: Right.

BP: The publisher called me the other day and said, “You want another book? I got a title.” I said, “What is it?” “How to Lose Two Billion Faster Than I Made One.”

JE: [Laughing]

BP: That is true. I lost two billion dollars in 2008. But I’m back up this year. Not back up to three-and-a-half billion, but I’m back approaching two. I’m doing okay.

JE: Very good. Thank you so much.

Chapter 15 – 0:28 Conclusion

John Erling: Now that Boone Pickens has talked about his life, we encourage you to read his autobiography, The First Billion Is The Hardest. It’s available in our bookstore section. You should also review our “For Further Reading” section. These Oklahoma stories are made possible by the generous contributions of our founding sponsors that are recognized in the “Our Sponsors” section of this oral history website VoicesofOklahoma.com.

Gallery

Production Notes

Interview with Boone Pickens

Program Credits:

Boone Pickens — Interviewee

John Erling — Interviewer

Mel Myers — Announcer

Honest Media

Mel Myers — Audio Editor

melmyershonestmedia@cox.net

Müllerhaus Legacy Website Team

http://www.MullerhausLegacy.com

Douglas Miller — Art Director

Mark DeMoss — Webmaster

Laura Hyde — Upload Coordinator

Date Created: August 6, 2010

Date Published: August 16, 2010

Notes: Recorded by John Erling in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Digital Audio Sound Recording, Non-Music.

Tags: Oklahoma State University, T. Boone Pickens, Dust Bowl, Henry Iba, Bulova watch, Gulf of Mexico, Oklahoma A&M, Time Magazine, Boots Adams, Ronald Reagan, Phillips Petroleum, Amarillo