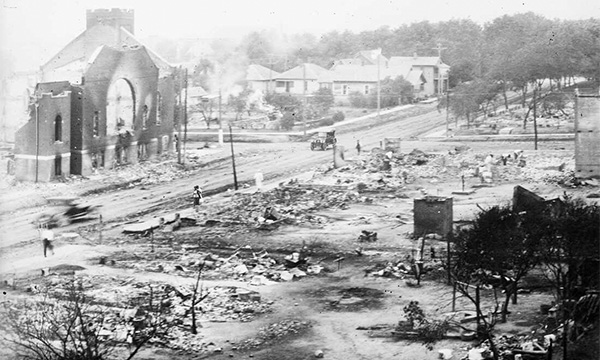

On May 31st, 1921, an indelible mark of atrocity and violence was left on the pages of Tulsa’s history. The once-thriving center of black commerce and culture, Tulsa’s Greenwood District, was destroyed by an angry white mob.

With hundreds of black Tulsans killed, thousands left homeless, and countless lives and homes uprooted and impacted by the violence, the massacre and its aftermath left incalculable suffering in its wake.

In our time together in this article, we’ll examine multiple aspects of the history of the Tulsa Race Massacre and its aftermath, including what sparked the initial events that led to that day of racial violence, how it was hidden from history for decades, the effects of the massacre on the black community, and how Tulsa’s Greenwood District is rebuilding and writing a new story of hope, strength, and reconciliation more than 100 years later.

What Caused the 1921 Race Massacre?

The root of the cause behind the race massacre was, in short, a lie. A lie that caught fire, was stoked by long-existing racial tensions, and swept up the entire Greenwood community.

It began on Monday, May 30th, 1921. A young black man, Dick Rowland, was a shoe shiner in downtown Tulsa. As Jim Crow laws — unjust laws that prohibited many black Americans from having the same rights as white Americans — were in effect in 1920s Tulsa, Rowland wasn’t able to use the “white” restrooms at his place of work.

Instead, Rowland, like many other black men and women who worked in the area, took an elevator to the “colored” restroom on the top floor of the nearby Drexel Building. It was that elevator that was operated by a young white woman: Sarah “Sarie” Page.

Though the exact details of what transpired are still in dispute to this day, the most widely-accepted account was Dick Rowland had tripped when entering the elevator and, to prevent falling, reached out for whatever he could hold on to. It was the arm of Sarah Page. Page let out a scream. Panicked, Rowland rushed out of the elevator and caught the eye of a white shop clerk on the first floor who called the police — and called the event an attempted assault.

Word spread quickly, eventually reaching the headquarters of The Tulsa Tribune. The headline rang out: “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in an Elevator!” These false claims, the resulting media wildfire, and the extremely tenuous racial discord endemic to Tulsa at the time made for the perfect storm.

Jenkin Jones Jr., longtime editor and publisher at The Tulsa Tribune, explains the racial landscape of Tulsa at the time:

“...It was a tough time in Oklahoma because the Klu Klux Klan was extremely strong. It’s been estimated that anywhere from 60 to 95 percent of Protestant ministers were involved in the Klan.

And the Klan really was two functions, it had all the bad elements of the Klan, anti-black, anti-Jewish, anti-Catholic. But in some small oilfield boom towns there was no law. So people, to run the prostitutes and the gamblers and the thieves out of town, joined the Klan and made that their concern. So the Klan was very big.

The majority of the legislature at one time was supposed to be Klansmen. You have to look at what happened in Tulsa against that kind of a background.”

— Jenkin Jones Jr.

Chapter 3

What Happened During the 1921 Race Massacre?

After being arrested by local police the following day, Tuesday, May 31st, Rowland was being held at the nearby courthouse in downtown Tulsa.

Having been whipped into a frenzy, a mob of angry white Tulsans gathered outside. Rumors abounded. The mob had made their intentions clear: They were there to break in, find Rowland, and lynch him.

Catching word of these claims, a throng of black Tulsans quickly gathered down at the courthouse — armed with rifles. Gunfire broke out, killing 10 white and 2 black people. Chaos broke out. The now outnumbered black men fled to the nearby Greenwood District.

Reaching a fever pitch, the hysteria was joined by false claims of this shooting being the start of a black insurrection. Hearing these cries on the wind, the white mobs grew stronger in number and in firepower.

The chaos and confusion continued to grow, finally culminating in the hellish morning of Wednesday, June 1st. White Tulsans descended upon Greenwood — burning and looting homes and businesses, razing entire blocks of the district to the ground, and even brazen murder of the unarmed. Even firefighters arrived to extinguish the blazes, they were met with threats of violence by the mob.

A survivor of the massacre, Otis Clark, shares some of his experiences on that day, including losing his home to the fires of the white mob, running for his life, and being shot at:

“...That’s right. Just across the Frisco tracks, on 1st Street, there was a mill. And the white men worked in that mill. It was some kind of grain mill, three or four stories high.

And they (white men) could get up at the top of that mill and look across the tracks and see what we colored folks were doing. And sure enough we got shot at from the men over across the tracks.

And it hit the boy in the hand, and I’m standing right behind him. He dropped his keys and we left the old car in the garage, and ran off and left it…”

— Otis Clark

Chapter 4

All told, more than 35 city blocks of Tulsa, Oklahoma were destroyed. According to the Red Cross, more than 300 black civilians were killed and more than 1,200 homes were burned. Libraries, hospitals, churches, hotels, and scores of businesses were looted, damaged, or destroyed.

Though thousands of black Tulsans were left homeless, jobless, and robbed of their community, there were never any local, state, or federal prosecutions issued in the aftermath.

What Stopped the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre?

The chaos and carnage of the race massacre continued until Governor James B.A. Robertson declared martial law — the temporary suspension of civilian government for that of military rule — over the city of Tulsa.

This declaration mobilized The National Guard to assemble in Tulsa. Unfortunately, their presence didn’t spell the end of the violence.

Though some of the details are contested even to this day, history shows there were guardsmen who sided with the views of the white mobs in Greenwood, deciding to help defend white communities — from a rumored counterattack by black citizens, which never materialized — rather than stop the looting and burning of Greenwood.

Soon after, more than 6,000 Tulsans — including many black survivors — had been rounded up in an internment camp set up at the local fairgrounds, where many were held for more than a week.

A survivor of the massacre, Wess Young, shares his childhood experience of being rushed from his home in the midst of the riot’s outbreak and held at the internment camps:

“Well, it was just a group of blacks. They only had the clothes that was on their back because when the riot started they had to run. They didn’t have time to pick up anything. They had to run to just get up.

And it started after twelve o’clock; the action started on the first of June. And they didn’t have time to get no more than the stuff they could put on. Had to get up, say, ‘Get up and get out of the house and go north.’”

— Wess Young

Chapter 4

How Was the Tulsa Race Massacre Hidden from the Public and Kept Secret?

It’s natural to assume that such a horrific event would be the focus of the nation's eyes and ears for quite some time. This, however, was not to be the case with the Tulsa Race Massacre.

Why? Because it became apparent — very quickly — to the business and political elite that a massacre such as this wouldn’t be a good thing for business, nor for the image of the city or the state. The cover-up was now afoot.

With regard to hiding the evidence of the physical violence and destruction, white mobs quickly dug mass graves and threw in the bodies of the murdered black Tulsans — no grave markers, no names.

On the media front, all record of coverage for the events had been burned, shredded, and quickly erased from the annals of their reporting history.

In the schoolhouses and institutes throughout Tulsa, there was no requirement to teach the events of the massacre nor mention it at all.

And within the homes and communities of the city, the massacre was never spoken about openly. The white Tulsans didn’t want to admit that they, or people they knew, were involved in the massacre, and the black Tulsans didn’t want to pass that pain down to the next generation — or risk the threat of violence from the Ku Klux Klan (KKK).

“Well, during that time, the Ku Klux Klan was blooming. They could shut up anything they wanted to. They could shut it down and then rumors and things. If you would talk, just like you and me talking here, to a black group, well, it wouldn’t go any further than this room. And then people in that room.”

— Wess Young

Chapter 5

In time, this led to entire generations of children never knowing the events of what unfolded on that horrific day. Over time, with it never being spoken of in schools or mentioned in history textbooks, it was nearly erased completely from the public consciousness.

How Did the Tulsa Race Massacre Re-enter the Public Discourse?

Beginning in the 1970s and 1980s, discussions of the Tulsa Race Massacre began to resurface in research publications. This renewed public interest eventually led to the formation of The Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921.

Their work, published in a final report in 2001, was a crucial element in re-opening the truth of this history to the rest of the nation.

In time, popular media publications, journals, and even television began to cover the events of the race massacre, opening the doors to public discussion after so many years. This re-entering of the race massacre into public knowledge led many Tulsans to realize they’d lived their whole lives in the city without ever knowing this aspect of its history.

These discussions soon after gave way to the forming of another commission — The 1921 Graves Investigation, formed by Mayor G.T. Bynum — dedicated to finding the many lost gravesites of the black Tulsans who lost their lives that day. It’s the hope of the commission that they can work to give some sense of closure to those who lost family members during the massacre and help uncover the truth that’s laid hidden away for so many years.

How has the Greenwood District Rebuilt after the Events of The Tulsa Race Massacre?

The Greenwood District, despite the generational pain and trauma inflicted by the massacre, has transformed into an incredible beacon of hope, racial healing, and community.

With inspiring voices, stories, and initiatives paving the way toward this new future, Greenwood’s rebuilding and flourishing has been made possible by black visionaries such as Julius Pegues, Chairman of the Board of the John Hope Franklin Center for Reconciliation:

“...And that's why we're building this John Hope Franklin Center for Reconciliation, where people can come together and dialogue about race. I mean, we have a lot of differences, but we have more things in common than we have differences. Once we come together, and talk about the things that we have in common, it will diminish the things that are different among us…”

— Julius Pegues

Chapter 9

Moreover, the Greenwood District has once again become — in the words of Senator Kevin Matthews — “an environment for fostering sustainable entrepreneurship and heritage tourism,” through initiatives and destinations like Greenwood Rising.

Now in the 102nd year since the events of the Tulsa Race Massacre, and despite the many hardships black Tulsans have faced, we see a Greenwood that is growing, sharing, and rising — rising to create a new era of community, prosperity, and working to remember the past while building a new future free of hate.

Conclusion

Despite the pain and suffering caused by the Tulsa Race Massacre, Tulsa’s Greenwood District is creating a fertile ground for reconciliation and healing. From what we’ve learned together today and what we’re seeing evidenced in Greenwood today, let’s revisit key takeaways from the wisdom of these influential voices:

The truth is always worth fighting for. It was through the fervent work of researchers, scholars, and other brave individuals who spoke truth to power that the events of The Tulsa Race Massacre re-entered the public discourse and eventually brought hope and healing to so many.

Even when things seem hopeless, healing is possible. From the tragedy of the Tulsa Race Massacre, we see incredible initiatives dedicated to healing and reconciliation all throughout the landscape of Greenwood, bringing inspiration and renewed hope to countless lives.

Our differences are so small compared to our similarities. There will always be people who try to point out differences in an attempt to alienate and divide. It’s up to us to recognize how small our differences are, how vast the similarities, and how we’re always stronger together.

Thank you for your time today in reading this article. Educational content like this and all of our work at Voices of Oklahoma is only made possible through the generosity of readers and listeners like you. With your support, we’re able to continue our mission to preserve and share Oklahoma’s history, one voice at a time.