Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher was a determined young woman whose courageous actions in the face of racial prejudice sparked a change that rippled across the nation.

Together, we'll delve into the remarkable life of Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher, a pioneering voice in the fight for equal education and a champion for civil rights.

We’ll learn about her early life and the motivations that underpinned her fierce determination for equality; we’ll dive into the landmark civil rights lawsuit against the University of Oklahoma, and her lifelong; and we’ll hear from the influential voices — her son included — whose lives were shaped by her bravery and leadership.

Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher’s Childhood and Early Life

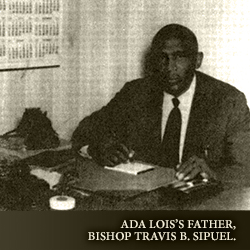

Originally hailing from Dermott, Arkansas, Ada’s parents, Travis “T.B.” Sipuel and Martha Bell Smith, fled from Tulsa to Chickasha in the wake of the Tulsa Race Massacre in 1921.

It was there in Chickasha that Ada was born just 3 years later in 1924, with her young life Her early life unfolded against the backdrop of a deeply segregated society and the challenges faced by African Americans in the Jim Crow era.

“JE: So we should say the State Constitution at that time would forbid the mixing of races in schools, African-Americans, blacks, all other persons, Indians, would be declared white.

BF: Yes. There was an organization called the Oklahoma Association of Negro Teachers. That organization was the African-American educational brain trust. And through that organization, teachers got jobs. African-Americans were educated.

They had separate teacher organizations so there was always a dual system of education. Blacks could not attend school with whites. White teachers could not teach black kids, black teachers could not teach white kids. There was total segregation and separation of the races.”

— Bruce Fisher, Son of Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher

Chapter 7

Despite the challenges imposed by society on black Americans during that time, the Sipuel family worked to become wealthy, owning multiple homes, cars, and even a home telephone — a rarity, at that time, regardless of race.

Thanks to her parents' hard work to give their children a better life, Ada and her brother, Lemuel, were more insulated from the racial injustices that plagued Oklahoma. This, however, did not protect her from the stark realities of this era of racial hatred entirely.

A horrific yet formative event in the life of young Ada was the lynching of fellow Chickasha native Henry Argo, a 19-year-old black man, and the last lynching that ever occurred in Oklahoma. Though she did not witness it directly, the news of the lynching — the practice of brutally hanging African-Americans that was sadly commonplace in the early 1900s — sent shockwaves through Ada’s community and family.

“JE: She was only five years old when that happened.

BF: Um-hmm (affirmative).

JE: But still it was a major impact.

BF: That had a big impact on her. She didn’t see the lynching, she was in the community—

JE: She felt it.

BF: …and felt the lynching. And it was similar with my dad. You know, he talked about that in Southwest Oklahoma, where they pick cotton and other things, he talked about occasions when the families would line the lower part of their shacks with two-by-fours and when.

And they heard the night riders coming; they would all lay on the floor. So that they would have some protection from the bullets and things.

My mom talked about the lynching in kind of the same way. Those were the two stories that I heard about that greatly impacted me. And she said that she knew something wrong and the men were getting their guns together and told them to stay inside and everything. So, yeah, that impacted her greatly.

JE: Well, back then, of course, the Klu Klux Klan was a very powerful force in the States. They promoted that agenda of violence.

BF: Absolutely.”

— Bruce Fisher, Son of Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher

Chapter 6

Though Ada was just 5 years old at the time of the lynching, the memories of its impact on her family and community never left her.

As Ada grew older and entered school, her headstrong and ambitious nature became clear to her teachers. Labeled “smart mouth” by many of her teachers, getting into fights --- even with the boys in her class — it was clear that Ada would never be one to back down from a challenge.

Her strong-willed and assertive nature led her to excellence academically, as valedictorian of her high school class and leader of the debate team; and musically, as a trumpet player and singer in the school band.

“Oh yeah. Yeah. You know, Mom used to always talk about that term, “smart mouth.” And how she used to get in trouble a lot because of that. What I saw and learned about my mom was how assertive she was.

And she would tell me that growing up she would get in rock fights with her brother. Her brother and her would get in rock fights with the kids and stuff, and so, she was never one to run from a fight growing up.

I mean, she’s always had that kind of personality. She would be with her brother and she felt with her brother, they could take on anybody. Even though she was the preacher’s daughter, which she wasn’t supposed to be doing these kinds of things, she was doing them.

JE: Well, that smart mouth, if that’s what we want to call it—

BF: Um-hmm (affirmative).

JE: …helped her because in high school she was on the debate team.

BF: Um-hmm (affirmative).

JE: In 1941, she was valedictorian of her class.

BF: Um-hmm (affirmative).”

— Bruce Fisher, Son of Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher

Chapter 9

These early memories of segregation and widespread injustice, coupled with her unquenchable desire for knowledge and never-say-die character, would serve her throughout her formative years in college and throughout the rest of her days.

Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher’s Collegiate Years

With a successful high school career under her belt, Ada looked toward higher education. However, due to the still-commonplace Jim Crow laws of that era that restricted white people and black people from attending school together, Ada’s options were restricted.

Initially, this leads her to Arkansas A&M in Pine Bluff, Arkansas — but not for long. She attends Arkansas A&M for only one semester.

“JE: Arkansas A&M, just a semester. And why just a semester?

BF: She says, and I’m not sure what the research pointed out, but what she said was that she wanted to be back home, close to home, and wanted to be close to where my dad was. See, my dad and her started dating. Warren Fisher was the best friend of Lemuel Sipuel.

They were best friends. That’s what got my dad into the Sipuel household in the first place. He was a good friend of the family. Again, my grandfather would have him chauffeuring him around the state. So my dad was a good friend.

So, Mom wanted to get back to where she was close to my dad. I don’t know what the research says about it but that’s what she told me.

JE: Well, she’s the best researcher. Right, right, right. But she goes to Arkansas A&M. She could not go to a public college here in Oklahoma.

BF: Correct.

JE: So she went out of state. And that was a black college then?

BF: Yes.

JE: Eventually though, she becomes a student at Langston University.

BF: Yes.

JE: And she marries your dad, Warren Fisher.

BF: Um-hmm (affirmative).

JE: March 3, 1944.

BF: There was only one institution of higher learning in the state of Oklahoma, that African-Americans could attend, and that was Langston University. The decision to come back home meant the decision to attend Langston. And so, that’s what she did.”

— Bruce Fisher, Son of Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher

Chapter 10

At Langston University, named after John Mercer Langston, the African-American congressman from Virginia, Ada faced new challenges — particularly those involved with the school being in such an underfunded state and, in turn, the students being forced to endure much worse conditions than those at white schools.

“There were two things that influenced my mom. She had a lawyer in the family and my mom, by the time she was a senior, she was a militant already.

She had fought for some changes at Langston as a student there and did something incredibly courageous that nobody else in the world did anything like. She could have suffered expulsion and everything else for it, which was sneaking into the president’s office and using his phone to call the state representative to complain about conditions at Langston.”

— Bruce Fisher, Son of Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher

Chapter 11

This same passion would carry her into one of the greatest challenges of her life and a hallmark moment not just for her own education and career, but for black Americans everywhere.

Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher’s Lawsuit Against the University of Oklahoma Law School

Following her graduation from Langston in 1945, Ada was ready to set her sights on law school. However, as Langston didn’t have a law program, nor were there any black colleges in the state that did

Having been inspired by Oklahoma civil rights icons like Roscoe Dunjee, the editor of The Black Dispatch and then-president of the NAACP, Ada was not about to let racial injustice deprive her — or other black Americans — of the best education possible.

Following Thurgood Marshall’s strategy to challenge segregated education throughout the United States — a strategy that Ada’s brother, Lemuel, was originally tapped to be a part of — Ada volunteered to lead the charge and seek admission to the University of Oklahoma Law School.

Dr. Bullock explained to my grandfather and my uncle what was about to happen, that they were getting ready to challenge the University of Oklahoma Law School. And they wanted my uncle to be the plaintiff.

He had just returned from World War II. He listened to what they said, he thought it was a good idea, but he said that he didn’t want to do it because he had just got through coming out of a fight that had postponed his life, put his life on hold for awhile to finish, and didn’t want to get involved with something else that would take up a considerable part of his life.

My mom is just sitting in the room listening to this. And she said, “Well, I’ll do it.” And that’s how she became the plaintiff because Dr. Bullock also knew about her and thought, “Well, okay, if we can’t get the first Sipuel we’ll get the second Sipuel.”

— Bruce Fisher, Son of Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher

Chapter 12

Sure enough, in January of 1946, Ada was rejected by the OU College of Law due to nothing more than her being black.

This rejection triggered a key step in Thurgood Marshall’s strategy to begin dismantling segregation in schools: With this being a law school, it would certainly draw more sophisticated and critical examination of the reasoning behind segregation laws. In turn, it was Marshall’s belief that the inherent injustice and barbarity of the Jim Crow era laws would be seen for the foolishness that they were, paving the way for segregation’s end.

This sparked the beginning of a three-year legal battle between Fisher and the University of Oklahoma College of Law, which eventually culminated in a hearing before the United States Supreme Court.

BF: Um-hmm, um-hmm (affirmatives). I can’t remember her talking about how the case was presented. But she said she could determine from the questioning that the state was not winning the case. She thought that from the time she heard the arguments that Thurgood’s case was so logical that they were not going to rule against them. But she had seen it happen before and was quite anxious to figure out how this was going to turn out.

But she talked about being with Thurgood and the lawyers. She went to the practice session at Howard University, the night before the case was presented. She said, “To be around all those lawyers who were testing strategies on how to present the case,” she said that was a phenomenal experience for her to witness that in preparation for this case. I don’t think very many people know that. But it was an awesome experience, she said, that night before.

JE: Then it took four days after the hearing before the court issued its ruling. So those had to be four agonizing days.

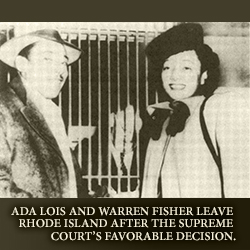

BF: Yeah, but as it turns out, pretty quickly in terms of Supreme Court how they work, that was very swift. She went back to Rhode Island after the case was presented and she lived with my dad up in Rhode Island when the decision was made.

JE: A one-page order that she was entitled to secure legal education afforded by a state institution. The court ordered that Oklahoma provide for the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment and provide it as soon as it does for applicants of any other group.”

— Bruce Fisher, Son of Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher

Chapter 17

The state, however, still entrenched in its backward “separate but equal” thinking during that time, sought to sidestep the ruling by opening the Langston University College of Law for black students rather than dismantling the racist practices of denying black students entry to OU’s law school.

Rather than acquiesce, Ada and her supporters stood firm. She was doing nothing less than attending OU rather than the sham school the state tried to establish instead.

Finally, after even more legal battles, with the sham law school at Langston mere weeks from running completely out of funds, and with OU recognizing that Ada would never back down, she was finally admitted to OU.

Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher’s Education at the OU College of Law

Despite being admitted, the racist treatment was on full display within the halls of the college. Forced to sit in a chained-off portion of the classroom marked “colored,” and even forced to sit in a separate area of the lunchroom marked and chained off similarly, Ada bravely attended her classes and soldiered on in honor of those who continued to support her.

During her time there, she was met with fervent support from many white students who criticized the blatant racism and injustice of her treatment.

JE: Even though she was finally admitted to the law school she had to dine in a separate, chained-off, guarded area of the law school cafeteria.

LJ: Yes.

JE: She recalled years later that some white students would crawl under the chain and eat with her when the guards were not around.

LJ: The students accepted her. It was the law of the university, it was the law of segregation. But the students, they took the chains down and accepted her and would not allow her to sit in a separate place to eat or to be in class.

— Loretta Young Jackson

Chapter 4

Graduating with honors in August of 1951. After years of valiantly fighting legal battles, and enduring the outright discrimination of the state and the tribulation it inflicted on her life, she was victorious.

And through this victory, a path was opened for the hallmark Brown V. Board of Education case wherein segregation of children was abolished from all public schools throughout the United States.

Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher’s Career, Service, and Achievements

Ada returned to Chickasha in 1952 where she practiced law for many years. Soon after, she once again enrolled at OU to earn her master’s degree in history.

Just 5 short years later, Fisher joined the faculty at Langston University as Chair of the Department of Social Sciences. She enjoyed a fruitful career at Langston, retiring in December of 1987 as the Assistant Vice President for Academic Affairs.

Following her retirement, Fisher was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters in 1991 and, just one year later, was officially appointed by Governor David Walters to the University of Oklahoma Board of Regents — the very school that rejected her for so many years.

Today, on the grounds of the OU campus in Norman, Oklahoma, you can find the Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher Garden, named in her honor, and which commemorates her victory with a powerful inscription:

“In Psalm 118, the psalmist speaks of how the stone that the builders once rejected becomes the cornerstone.”

Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher’s Lasting Impact on Oklahoma

Whether you’re an aspiring law student, embarking on a new venture, or anyone in between, when we examine the life of Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher, there are indelible lessons that we can learn from her legacy and apply to our own lives.

-

There’s tremendous power in perseverance. Fisher's unwavering determination in the face of blatant discrimination serves as a powerful testament to the transformative potential of perseverance. Her steadfast pursuit of justice through the legal system, despite the challenges and obstacles she faced, ultimately paved the way for positive change.

-

Injustice must be challenged. Fisher's story exemplifies the courage it takes to stand up against injustice and fight for what is right, even when the odds are stacked against you. It won’t change unless you take a stand.

-

Just one person can make all the difference. Fisher's legal battle had a profound impact that extended far beyond her own life. Her victory in Sipuel V. Board of Regents not only secured her own right to an education but paved the way for the abolition of school segregation through Brown V. Board of Education.

Thank you for being with us as we took a closer look at the life, legacy, and lasting impact of Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher.

These Learning Center articles continue to enrich the lives and curriculums of thousands of students and educators all throughout the country, and it’s all thanks to the generous support of readers like you.

Educational content like this and our ever-growing collection of oral histories from influential Oklahomans is only made possible by gifts from readers like you.

A gift of any amount helps us continue our mission to preserve, protect, and share the voices and stories of Oklahoma’s people and history.