Women’s History Month is the time our nation dedicates to reflecting on the incredible contributions and achievements of American women throughout the history of our nation.

It is a time of gratitude for the efforts of these remarkable people as well as a reflection on the essence of the American spirit: that anyone, regardless of their background, race, creed, or color of skin can achieve their goals in the United States.

In our time together in this article, we’ll learn about how women’s history month began, the incredible women who helped shape Oklahoma history — as well as the history of our nation — and the lessons we can learn from them and apply to our own lives.

How Did Women’s History Month Start?

Throughout most of American academic history, the achievements of women throughout history was largely an untouched subject in schools. In turn, this led to a general unawareness of the contributions of women throughout history within the general public.

In 1978, the Education Task Force of the Sonoma County Commission set out to create a week-long event to celebrate historical women and their tremendous influence throughout history. This became the first “Women’s History Week.”

Over time, this movement to celebrate the historical achievements of women grew; and in 1979, Molly Murphy MacGregor, a member of that same Sonoma County group in California, was invited to the Women’s History Institute at Sarah Lawrence College.

The institute, chaired then by Gerda Lerner, brought together the country’s most distinguished and dynamic women leaders of womens’ and girls’ organizations throughout the country. Working alongside MacGregor and learning of the success of Sonoma County’s Women’s History Week, the institute agreed: It was time to secure a nationally-recognized Women’s History Week.

The first steps in championing this new initiative came in February of 1980, when President Jimmy Carter declared that the week of March 8th, 1990 was to be enshrined as National Women's History Week.

“From the first settlers who came to our shores, from the first American Indian families who befriended them, men and women have worked together to build this nation.

Too often the women were unsung and sometimes their contributions went unnoticed. But the achievements, leadership, courage, strength and love of the women who built America was as vital as that of the men whose names we know so well.

As Dr. Gerda Lerner has noted, ‘Women’s History is Women’s Right.’ – It is an essential and indispensable heritage from which we can draw pride, comfort, courage, and long-range vision.”

I ask my fellow Americans to recognize this heritage with appropriate activities during National Women’s History Week, March 2-8, 1980.

I urge libraries, schools, and community organizations to focus their observances on the leaders who struggled for equality – – Susan B. Anthony, Sojourner Truth, Lucy Stone, Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Harriet Tubman, and Alice Paul.

Understanding the true history of our country will help us to comprehend the need for full equality under the law for all our people.

This goal can be achieved by ratifying the 27th Amendment to the United States Constitution, which states that ‘Equality of Rights under the Law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.’”

— President Jimmy Carter

Read Full ProclamationFollowing President Carter’s declaration, the cause was further supported in the halls of Congress by Representative Barbara Mikulski and Senator Orrin Hatch, who co-sponsored the first Joint Congressional Resolution (Pub L. 97-28) in support of National Women’s History Week in 1981.

The spark was lit. Throughout the nation, states were celebrating the week and classrooms — teachers and students alike — were enthusiastically supporting and celebrating historical women. The movement continued to sweep through the nation like wildfire, with school boards, community groups, local city councils, and everyone in between calling for local celebrations of Women’s History Week.

Over time and as more towns, cities, counties, and states rallied together in support of Women’s History Week, it became abundantly clear: The time for a National Women’s History month was here.

Spearheaded by the National Women’s History Alliance, and the thousands of individuals and groups that joined alongside their efforts, yearly lobbying efforts were carried out for this national recognition.

By the mid 80’s, 14 states had independently marked March as Women’s History Month. With this combination of continued grassroots support, national lobbying efforts, and widespread adoption at the state and local level, the case was made before Congress that a National Women’s History Month was clearly needed.

Recognizing the support by the vast majority of Americans, and the educational and inspirational benefits for girls and women across the country, Congress declared, in perpetuity, March as National Women’s History month in 1987.

Every year, even as of this writing, there is a special Presidential Proclamation issued in recognition of the extraordinary achievements and historical influence of our country’s women.

In What Ways Have Oklahoma Women Shaped History and What Lessons Do They Pass on To Future Oklahoma Women?

In honor of the theme of 2023’s Women’s History Month — “Women Who Tell Our Stories” — we wanted to bring the voices and stories of these incredible Oklahoma women to readers like you.

Naturally, though the voices featured here can’t hope to encompass every contribution by every woman in these historical topics, we’d like to briefly journey together to see how these incredible women have impacted our state, our nation, and the world.

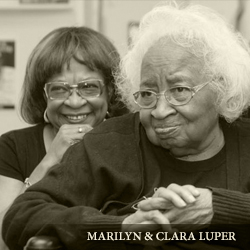

Civil Rights: Clara Luper

In 1958, Clara Luper and her students from the Oklahoma City NAACP Youth Council were invited to New York City to perform the play she wrote, Brother President, about Martin Luther King Jr.

It was this trip that Clara led which became the catalyst for the beginning of the sit-in movement in Oklahoma City and the country.

One of Clara’s students was her daughter Marilyn Luper Hildreth. It was seven-year-old Marilyn who in a meeting suggested the group go down to the Katz Drug store to order a Coke and some burgers.

Clara Luper’s Advice to Girls and Women (as told by Marilyn Luper):

“What would I like for the young people to take away today? You can make a difference.

It doesn’t matter your age, because we were young. It doesn’t matter your religious background or anything else. If you want to stand up for something, if you see injustice, fight against it, don’t be a wimp.”

— Marilyn Luper

Chapter 11

The date was August 19, 1958, and it became the nation’s first nonviolent lunch counter sit-in. On the third day, Katz staff served the group burgers and Cokes. The Katz chain soon ended its segregation policy in all thirty-eight of its stores in four states.

Adults were not used for the sit-in for fear of violence. But it was the thirteen children of the youth council ranging in age from seven to fifteen who endured insults, threats, and even spit from angry white customers.

The spark that Luper ignited paved the way for civil rights leaders then — and for future generations — to bravely stand up for equality and equal treatment regardless of the color of someone’s skin.

Media and Communications: Joyce Jackson

Joyce Jackson was in Junior High School when she became part of the Katz Drugstore sit-in in 1958, the beginning of a movement that contributed to race relations reform in Oklahoma.

Joyce was the first black woman on television in Oklahoma at KOCO 5, Oklahoma City, becoming an award-winning broadcast journalist, producer and talk show host.

In 1982 she began a career in the Oklahoma Department of Justice as a public relations officer until 1997 when she left the agency to become the Communications Director for the Illinois Department of Corrections. She returned to the Oklahoma Department of Corrections as the Executive Communications Administrator in 2005.

Joyce also worked as a professional model for 20 years and was the owner of a modeling/charm school.

She retired from the Oklahoma Department of Corrections in 2014 after 24 years of service.

Joyce Jackson’s Advice to Girls and Women:

“My advice is to dream big and to know that the world is open to you today — like it's never been open to you before. And you have the right, and you have all of the resources available to you.”

— Joyce Jackson

Chapter 17

Activism: Carrie Dickerson

When Carrie Dickerson first saw a newspaper headline about the electric company’s plans to build a nuclear power plant near her home in Inola, Oklahoma, she knew little about nuclear reactors and less about the legal process through which they were built and operated.

To learn more, she asked the Atomic Energy Commission to send her all the information they had on nuclear energy. Carrie received stacks of documents which she read over the next few months turning her worry about nuclear energy into determination. She would fight to stop the Black Fox plant with all the resources she had.

Before it was over the fight would cost her and her husband Robert their entire savings, their nursing home, and almost the family farm.

Ultimately, her fight ended in triumph, halting the building of the Black Fox Nuclear Power Plant.

Carrie Dickerson’s Advice to Girls and Women (as told by daughter Patricia Lemon):

“Follow your conscience. Respect other people’s ideas, but do not be governed by them.”

— Patricia Lemon

Chapter 15

Art: Joy Harjo

U.S. Poet Laureate Joy Harjo was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma and is an enrolled member of the Muscogee Creek Nation.

She is the daughter of a Creek father and a Cherokee-French mother. Her father was a sheet-metal worker from a famous Creek family. His great-grandfather was a Native American leader in the Red Stick War against President Andrew Jackson in the 1800s. Harjo’s mother was a waitress of mixed Cherokee, Irish, and French descent.

Growing up, Harjo was surrounded by artists and musicians, but she did not know any poets. Her mother wrote songs, her grandmother played saxophone, and her aunt was an artist. These influential women inspired Harjo to explore her creative side. Harjo recalls that the very first poem she wrote was in eighth grade.

However, Harjo did not start to write professionally until later in life. She became a writer, academic, musician, and Native American activist whose poems feature Indian symbolism and history. Her poems also deal with social and personal issues, notably feminism, and with music, particularly Jazz.

In 2019, Harjo was elected a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets and became the first Native American United States Poet Laureate from the Library of Congress. She has also written several film scripts, television plays, and released five albums of original music. In 2009, she won a NAMMY (Native American Music Award) for Best Female Artist of the Year.

Joy Harjo’s Advice to Girls and Women:

“When you be yourself, it is not always that easy. Sometimes you come up against rules. It can be difficult to be the only person doing what you’re doing.”

— Joy Harjo

Chapter 11

Education: Nancy Feldman

Nancy (Goodman) Feldman grew up in a suburb of Chicago, Illinois, and graduated from the University of Chicago with undergraduate and law degrees. After completing her degrees, she married Ray Feldman and moved to Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1946.

Nancy became known as an activist for many causes. She took on integration in Tulsa and lobbied for the first black student to be admitted to Holland Hall. As a professor at the University of Tulsa, she included the 1921 race riot in her curriculum and was told to ignore the subject, but she continued teaching it anyway. Nancy challenged dairy companies who delivered milk to Tulsa Public Schools to date their milk containers. She also led the charge to expand arts education in Tulsa Public Schools.

Nancy founded The Center for Individuals with Physical Challenges and the International Council of Tulsa, which would become Tulsa Global Alliance.

A long-time educator, Nancy retired from the University of Tulsa after a thirty-seven year career teaching in the Department of Sociology. She served nationally on many boards including the National Space Institute.

Nancy Feldman’s Advice to Girls and Women:

“I had a lot of lectures and they were always planning. I’m going to do this, then I’m going to do this and then I’m going to do this and I say don’t get yourself in lockstep. Keep open to all the opportunities that come by and grab them, even if they hadn’t been on your list. I never thought I’d marry and live in Tulsa.”

— Nancy Feldman

Chapter 14

Community Leadership: Loretta Young Jackson

Verden, Oklahoma resident Allen Toles was an African American farmer who had become the owner of his land through the Homestead Act of 1862. He built Verden Separate School on his property in 1910 as a school for black children. When the school was consolidated with Lincoln Separate School in Chickasha, the school was no longer used except as a workshop and storage building.

About 90 years later, the abandoned schoolhouse was found by Loretta Young Jackson and under her guidance the school was moved to Chickasha where it stands on Ada Sipuel Ave. The school is visited by hundreds of students each year and serves as an education tool on race relations.

The school was restored and later placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2005.

Loretta worked in the area of real estate and mortgage banking and became a leader on public issues in Chickasha and the state. Among her many accomplishments she is the founder of the Loretta Jackson African American Historical Society.

Loretta holds many honors for her all her accomplishments but perhaps her greatest work lies in the discovery and restoration of that one room separate school.

Loretta Young Jackson’s Advice to Girls and Women:

“No, there is no “I can’t” in my mind. I will find a way, there is a way to accomplish whatever comes before me.”

— Loretta Young Jackson

Chapter 16

Business & Entrepreneurship: Lilah Marshall

Cornelia’s Ala “Bama” Marshall’s homemade pies were so mouthwatering and so well known. that people lined up on the sidewalk outside Woolworths soda fountain door, waiting for a single slice of that famous homemade pie.

In 1937, Bama’s son Paul Marshall and wife Lilah moved to Tulsa, Oklahoma and started a full-fledged pie making business.

Today, The Bama Companies can produce more pies in a single day than Alabama Marshall could have made in a lifetime.

In this interview you will hear Lilah Marshall tell the story of hard work, drive and determination to make ends meet that led to the success of Bama Pie. Lilah was 93 on Nov. 9th, 2009 when she shared her memories of Big Momma and Big Daddy, her husband Paul and the journey of Bama Pie.

Today, Bama Pie offers custom-made, oven-ready products to customers in more than 18 countries using production facilities in the U.S. and abroad.

Lilah Marshall’s Advice to Girls and Women:

“Well, they just should know that they really want to do it and then find out all the ways they can get into it, the easiest way and the cheapest way. Go from there. Learn the way. They have to make their own way. It would be a different way probably then we made it, but they will figure it out.”

— Lilah Marshall

Chapter 8

History: Angie Debo

Oklahoma’s “greatest historian” was nine years old when she first set foot on Oklahoma soil on November 8, 1899, having arrived by covered wagon with her family from Kansas. Angie Debo described that day as a beautiful golden autumn morning—“The sky was clear blue, and green wheat stretched to the horizon.”

Her new home town was Marshall, Oklahoma, which did not have a four-year high school before 1910, so she was twenty-three when she graduated in 1913. Five years later, she earned a bachelor’s degree in history from the University of Oklahoma and in 1924 a master’s degree from the University of Chicago. She received a Ph.D. in history from Oklahoma in 1933.

But even with a Ph.D, Angie Debo would never hold a position in a history department at a university, largely due to gender discrimination.

Debo turned to writing American Indian history and among her many discoveries she learned that much of eastern Oklahoma was dominated by a criminal conspiracy to cheat Indians out of their property. Her findings were published under the title: And Still the Waters Run.

She wrote, edited, or coauthored thirteen books in her lifetime. In 1985, in recognition of the various contributions she had made to American Indians, to her state, and to her profession, Oklahoma placed Debo’s portrait in the state capitol rotunda.

Angie Debo’s Advice to Girls and Women (as told by Dr. Patricia Loughlin):

I think she would ask them to join her. I think she would encourage them to write more, to share their work, to speak up in class, to ask questions, to take advantage of opportunities that your teachers provide to you, or your parents, or your community members, to get out there and visit places in the state of Oklahoma and think about the history of our state and be proud of it.

She would also encourage people to get out of Oklahoma sometimes and to travel throughout the country and visit places in the world when you have the opportunity.

And she would say, “Live a full life, ask questions, speak up, share your expertise with others, and do not give up.”

— Patricia Loughlin

Chapter 16

Law: Stephanie Seymour

Judge Stephanie Kulp Seymour, who joined a historic class of women judges in 1979 when she was appointed to the Tenth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals, was encouraged early on by her parents to be an independent thinker.

While a youngster, she and her sister received the same encouragement as their two brothers. Seymour attended integrated public schools in Battle Creek, Michigan, but was home-schooled during long family trips around the country and overseas.

Seymour had hoped to attend Harvard or Yale, but those Ivy League colleges did not accept women as undergraduates in the 1950s. Seymour believes now that Smith College, an all-women’s school in western Massachusetts, better prepared her to compete among men after her graduation. She graduated from Harvard Law in 1965 where a recruiter told her he had no interest in hiring women. She later became his firm’s first female lawyer. When she moved to Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1966, there were only five practicing female lawyers.

Upon her appointment to the Tenth Circuit U.S. Appeals Court in 1979, Judge Seymour became its first female judge, and later its first female chief judge. She assumed senior status in 2005.

Stephanie Seymour’s Advice to Girls and Women:

“You’ll have a lot easier time than I did. Because there are now a lot of women lawyers.

But I guess my message includes, “Don’t give up your family life,” because I had four children over time. I worked part-time. I worked four days a week for a number of years when I was a lawyer. I took off six months, there was no maternity leave back then. I just took off. But my work firm was always fine with that. They didn’t really know what to do with me, so I just sort of created rules as I went along. It is very possible to have a family life and practice law.

One of the things I say is there should be more women starting their own firms because then they would have control over that. But the system is much better than it used to be and a lot of firms have maternity leave. And if they don’t, you can take three months off without pay, under federal law now. So having a balanced life is great.”

— Stephanie Seymour

Chapter 14

Remembering and Celebrating Oklahoma’s Influential Women

Though the stories we shared today just barely scratch the surface of all of the many achievements of Oklahoma’s women, we hope the lessons passed on by these influential women inspire you to accomplish all you set out to do in life.

Thank you for your time and for enjoying this learning experience together with us. Educational content like this is only made possible by the generous support of readers and listeners like you. Gifts of any amount help us continue our mission to preserve and share the stories of Oklahomans one voice at a time.